Birthday Special: My Favorite Poems

Sorry, beautiful watchers, no birthday retrospective this year. It didn’t feel right to start another one while my Jurassic Park retrospective is still in limbo. Instead, I’ve decided to present another college writing assignment that I wrote for a poetry class during the fall 2016 semester. However, this one will work a bit differently than I did with the other college essays I’ve posted here and on DeviantArt.

For one thing, this assignment isn’t an essay but a compilation of thirteen poems. It was part of an end-of-semester project where the professor had us choose several poems we liked and assemble them into an anthology. I believe she allowed us to center our picks around a theme. The theme I chose was existentialism and humanity’s relationship with forces beyond our control. I blame this obsession with existentialism on the tension between my Christian upbringing and the new educational opportunities I was exposed to in college. However, the then-incoming Donald Trump administration almost certainly played a part in it as well, as my faith in the country I was born and raised in slowly began to crumble before my eyes (his somehow winning a second term last year certainly didn’t help matters).

It would probably be easy to simply copy the poems here and leave it at that, but I feel that would be boring (and also possibly violating copyright law for several of them). Instead, I’d like to share my personal opinions on each piece, and perhaps also discuss how I discovered them, why I chose them for the anthology, and maybe talk about how my relationship with each one has changed in the decade since I compiled the anthology. I think that would be a fun way for you to get to know me better as a special birthday treat.

So without further ado, here’s the original intro for the anthology collection.

The poems I collected for this anthology examine humanity’s relationship with everything bigger than us. This includes our relationship with nature, time, evil, technology, our own existence, the universe, and God. Basically, the poems I collected here deal with humanity’s place in the universe and where our destiny lies.

The first two poems, “The Tyger” and “Emptiness,” speculate on our relationship with God and his creations. Another poem, W. B. Yeats’ “The Second Coming,” asks what humanity would do if the gods turned out to be eldritch monsters rather than the angelic beings portrayed in old art. Other poems in the anthology deal with our relationship with humanity as a whole, both its good and bad aspects (like “Troll” and “Christmas Bells”). Still others talk about remembering how we should be mindful of the things in the world that are bigger than us, either by showing us a world where the hand of man has been erased entirely (like “Ozymandias” or “There Will Come Soft Rains”) or by telling us to remember how fragile yet important our species is (like “The Answer” or the aptly named “Remember”). Finally, there are the poems that address our pursuit of meaning in our existence or just pursuit of happiness in life, like “El Dorado,” “To the Virgins, Make Much of Time,” “Nothing Gold Can Stay,” and the final poem, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came.”

I have been interested in existentialist-type subjects for a while now. I believe this interest stemmed from my religious upbringing and the many new things I have learned during my tenure at SUNY Potsdam. It may also have to do with the fact that I strongly believe in evolution despite being a practicing Christian, so I am not as sure that we are as important in God’s grand design as some of my fellow Christians would believe. Either way, it is both frightening and exciting to imagine what our place in the universe really is.

The Tyger by William Blake

I was first exposed to this poem long before I entered college in an elementary music class, where the teacher had us sing a musical version of it for the end-of-the-year concert we would do annually before summer break. There have been many musical adaptations of the poem in the centuries since it was first written, and I don’t know the specific one our version was based on. Still, it’s an interesting choice to introduce such a young audience to a poem full of such heady philosophical and religious questions.

William Blake originally published it in his 1794 illustrated collection Songs of Experience, which was combined later that year with his earlier collection Songs of Innocence. The two collections were his first forays into the explorations of religion and spirituality (which combined a Marcionite Gnostic form of Christianity with influence from the prophetic works of Swedish mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg) that would inform much of his work going forward and helped establish him as one of the most important figureheads of the Romantic movement.

Songs of Innocence and Experience were the first works of Blake to express his idiosyncratic views on the nature of innocence and sin. He believed that humanity’s struggles came not from original sin but from the battle between the contrary aspects of their nature. This is perhaps best explained in Plate 3 of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence.

From these contraries spring what the religious call Good & Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason. Evil is the active springing from Energy.

Good is Heaven. Evil is Hell.

Perhaps the best way to explain what “The Tyger” is talking about is to compare it with “The Lamb,” its sister poem from Songs of Innocence. Blake observes the differences between the ferocious tiger and the delicate lamb and ponders how the same God could possibly be responsible for creating both creatures. He asks the tiger (and, by extension, the prime mover) when, where, why, and how the tiger first came into being. He also wonders how the creator reacted when he first saw the tiger (“When the stars threw down their spears/And watered Heaven with their tears/Did he smile his work to see?/Did he who made the lamb make thee?”), and gradually grows more accusatory as the poem reaches its end (“What immortal hand or eye/Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?”).

It kind of makes you wonder how Blake might have reacted had he lived long enough to see the discovery of T. rex or Megalodon or any of the other large prehistoric predators we’ve discovered in the two hundred years since his death.

Emptiness by Rumi

This is by far the oldest poem in my collection. It was composed in the 1200s, during the time Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi, or just Rumi for short, traveled throughout the Muslim world, using his poetry to spread his unique vision of Sufi mysticism. His verses have since become so popular that he has become not only one of the most popular poets worldwide but also the best-selling poet in the United States.

I’ll be honest, though: I had never heard of Rumi until I compiled this anthology. I do remember being surprised at learning how popular he was in the States, since I was aware of how normalised Islamophobia was in my country even then (and honestly still is, if many of my fellow citizens’ blasé reactions to the Gaza genocide are any indication). I’m fairly certain I simply chose “Emptiness” at random while scouring the Internet for poems from this guy to see if he was worth the hype. As I’ve grown increasingly familiar with his work and the spiritual traditions he operated within over the years, I’ve increasingly understood why he’s so beloved.

Perhaps this Time magazine article by Ptolemy Tompkins best summarizes the spiritual worldview that Rumi was trying to express through his work:

For Rumi, the universe is like a tavern where people, drunk with desire and longing, collect and carouse until they finally remember their true calling: return to an Islamic God whose all-encompassing love is the core of every earthly love from the most trifling to the deepest and most passionate. “Where did I come from, and what am I supposed to be doing?” Rumi had asked. “I have no idea. My soul is from elsewhere, I’m sure of that, and I intend to end up there.”

Despite holding the Islamic faith as superior to all others and describing Christianity as “overloading the image of God with superfluous structures and complications,” Rumi also expressed ideas of religious pluralism in his work. He has been quoted as saying:

The Light of Muhammad does not abandon a Zoroastrian or Jew in the world. May the shade of his good fortune shine upon everyone! He brings all of those who are led astray into the Way out of the desert.

-Gamard, Ibrahim (2004). Rumi and Islam. SkyLight Paths. p. 163.

Rumi tends to infuse even the most mundane of objects with intense spiritual imagery in his poems, to the point that some, like Reza Aslan in his 2017 book God: A Human History, have referred to him as a pantheist (someone who believes that God and the universe are one and the same). Indeed, one could argue that Rumi was the William Blake of his day; a free-spirited individual who chafed against the orthodoxies of his Abrahamic faith while still a devoted follower. They even shared a fascination with the contrary aspects of human nature (something illustrated in “Emptiness” by lines like “Fighting and peacefulness both take place within God”). It’s probably not a one-to-one comparison, though; Blake’s impact on mainstream Christianity is practically nonexistent, whereas Rumi is so revered in Islam that many consider his epic poem, the Masnavi, second only to the Quran as the greatest work of Islamic literature.

As for the poem I’m talking about here, I think that what Rumi was getting at in “Emptiness” is similar to the Masao Abe quote I used as the header for this section. True, Abe is speaking from a Japanese Buddhist perspective, but I think both men are trying to make the same argument: humans are blank canvases that gradually define themselves by their actions as they move through their lives on Earth. At the same time, Rumi clarifies that some actions are holier than others. For instance, “Honor your friend. Or treat him rudely and see what will happen!” Or, “One hand shakes with palsy. Another shakes because you slapped it away. Both tremblings come from God, but you feel guilty about one, but what about the other?” He also bluntly states that, “Ignorance is God’s prison. Knowing is God’s palace.”

Basically, kindness and knowledge are the keys to a healthy life, both physically and spiritually. We all have free will, so use it wisely.

Eldorado by Edgar Allen Poe

Edgar Allen Poe is better remembered today for his gothic horror-themed stories and poems. However, he also made works that are not quite so full of doom and gloom. “Eldorado,” first published in Boston’s The Flag of Our Union paper in April 1849, is a bittersweet lament about the difficulties of finding happiness in a world that so often seems bent on denying it to us. It might also be considered a swansong to Poe’s writing career, as he died just six months later at only 40 years of age.

The poem is a short narrative piece consisting of four six-line stanzas. It follows a “gallant knight” searching for El Dorado, a legendary city of gold said to lie somewhere in the rainforests of South America. The knight starts out bright and optimistic, singing as he goes, but soon grows older and more cynical as he fails to find any trace of the golden city. Just as he starts to give up, however, he stumbles across a ghostly pilgrim who knows where El Dorado is, and points him in the right direction (“Over the mountains of the moon, down the valley of the shadow, ride! Boldy ride,” the shade replied, “if you seek for El Dorado!”).

It has been speculated that the California Gold Rush of 1849 was the direct inspiration for this poem, something which seems to be confirmed in a letter Poe wrote to a friend of his that February:

Depend upon it, after all, [Frederick W.] Thomas. Literature is the most noble of professions. In fact, it is about the only one fit for a man. For my own part, there is no seducing me from the path. I shall be a litterateur, at least, all my life; nor would I abandon the hopes which still lead me on for all the gold in California.

Poe is likely repeating the age-old moral that happiness cannot be found in material objects but rather in something more spiritual and transcendent. Indeed, there are hints in the poem that El Dorado might be a stand-in for Heaven or a similar blissful afterlife, especially the reference to Psalm 23 in the fourth stanza (“Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.”) and the fact that the knight has to pass over “the mountains of the moon” to reach it.

Another interesting feature of the poem is that the third line of every stanza ends in the word “shadow” (fitting for one of the greatest horror writers of all time). First, the word shows how the knight rides day and night (or “in sunshine and in shadow”) in search of the city. Next, the word denotes his depression as he reaches the end of his life with nothing to show for his efforts (“And o’er his heart a shadow”). Then the word signifies the ghostly nature of the pilgrim the knight meets (“He met a pilgrim shadow”), which, given the context, might mean the pilgrim has met the grim reaper. Finally, the word is used in the aforementioned Psalm 23 reference, possibly indicating the knight’s journey to find happiness in the hereafter.

Indeed, I feel like I am the knight in the poem in some ways, in that I feel like my best life is lost somewhere beyond the horizon. I’m currently stuck living with family members that I can’t relate to anymore, and my best option for escaping (a driver’s license) has been thrown into question because that orange idiot that my parents voted for doesn’t understand how auto tariffs work. But that doesn’t mean I’m just going to lie down and surrender. I know one day I will ride, boldy ride, until I find my El Dorado.

Ozymandias by Percy Bysshe Shelley

Percy Shelly may be somewhat overshadowed by his wife, Mary, these days on account of her creating Frankenstein’s monster. Still, he has nevertheless left behind an equally formidable literary legacy as one of the leading poets of the Romantic movement. How ironic, then, that his most famous work, first published in the London newspaper The Examiner in January 1818, is about how even the mightiest works of humankind will gradually fade to nothing in the sands of time.

This deceptively simple poem, consisting of a single fourteen-line stanza, tells of how the narrator learned of a curious ancient ruin courtesy of “a traveller from an antique land,” who describes it as “two trunkless legs of stone”. At the same time, “a shattered visage lies” on the ground below them, with a facial expression bearing a “frown and wrinkled lip and sneer of cold command.” Accompaning this wreckage is an inscription that reads, “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings! Look upon my works, ye mighty, and despair!” But the threat is undermined by the fact that this broken statue is all that remains of his presumably vast empire, while “round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, the lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Ozymandias and the traveller are actually based on real people. The former is the Greek name for the great Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II (who reigned from 1279-1213 BCE), while the traveller is based on Diodorus Siculus, a Greek historian from the 1st century BCE. Choosing Ramesses the Great as the subject of this poem may seem strange, considering that his legacy is still celebrated in Egypt even today. Still, it’s evident that the sands of time have long since beaten the once gleaming temples of ancient Egypt into a shadow of their former selves, even if the ruins are still more substantial than what Shelley describes in the poem. It certainly helps his case that Ramesses the Great is often held to be the pharaoh who served as Moses’ antagonist during the events of the Book of Exodus (although most historians agree that the story has no basis in historical fact). It also helps that the famous “I am Ozymandias” inscription was based on an actual statue of Ramesses that Diodorus saw in his lifetime, which has likely long since been lost.

“Ozymandias” is probably best appreciated as a mocking indictment of the hubris of empire-builders, whether they be the Egyptians and Romans of old, the imperialist British Empire Shelley grew up in, or the modern-day American Empire that I and many others are convinced is rapidly approaching the end of its natural lifespan.

The Answer by Robinson Jeffers

Pictured: Jeffers

I first learned about Robinson Jeffers from (of all things) Ghost Adventures. In a 2012 episode of the hit Travel Channel show, Zach Bagans and company traveled to Jeffers’ famous Tor House in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, to see if a prediction Jeffers made in his poem “Ghost” that his spirit would return fifty years after his death came true. If I recall correctly, they captured a misty figure ascending the stairs in Hawk Tower on a thermal camera.

While I’ve long since lost interest in Bagans and his supernatural snipe hunts, Jeffers has continued to occupy a space in my curiosity. When it came time for me to track down poems for this anthology, I scoured the Internet for an appropriate Jeffers poem to include and eventually settled on “The Answer,” composed in 1936.

Appropriately for a period of time when Hitler’s Third Reich was ascendent and Stalin’s Great Purge was starting to ramp up, the poem attempts to advise the reader on how to behave when civilized society starts crumbling around you. Overall, Jeffers proposes three main ideas for how to keep one’s humanity in these trying times. First, avoid ending in violence as much as possible and align yourself with a nonviolent political faction (or, failing that, the least violent). Second, try not to get caught in “dreams of universal justice or happiness,” lest you get disappointed when those dreams go unfulfilled. Third, stop seeing yourself as separate from nature and the universe, for if you start seeing yourself or humanity as a whole as superior, you risk falling for the same civilizational maladies that put us in this situation in the first place.

In my opinion, some aspects of this poem have aged better than others. The part about not seeing humanity as separate from nature is something I wholeheartedly agree with. Indeed, Jeffers even coined a word for this belief, “inhumanism,” which argued that humanity was too self-centered to appreciate the wonders of the universe that surrounded them and that they needed to decenter themselves from the “great chain of being” style of thinking that had dominated for centuries. In the answer, he even goes as far as to compare a person severed from their spiritual connection from their natural surroundings to a severed hand, calling it “an ugly thing…atrociously ugly.”

On the other hand, the “these dreams will not be fulfilled” passage kind of rubs me the wrong way. It seems to imply that Jeffers thought humanity was incapable of setting up a more just system than the ones that existed in 1936, which strikes me as overly pessimistic. One only has to read books like A Paradise Built in Hell and Humankind: A Hopeful History to see that humanity is far more capable of kindness and solidarity than most greedy business leaders, right-wing demagogues, and religious fundamentalists would have us believe, even in the face of horrifying disasters.

I have mixed feelings about the part about avoiding violent political parties. While I agree about avoiding violence as much as possible, I do wonder about certain populations who might not have that luxury, like the Palestinians currently suffering under Israel’s viciously genocidal Gaza war. Indeed, considering how hard Trump and the Project 2025 architects are working to turn the United States into an authoritarian dictatorship, I wonder if one day in the not-too-distant future, I might have to take up arms to stop our country from backsliding into a new Jim Crow era. Hopefully, Trump will die, and his MAGA movement will fizzle out without his charisma to wind them up before that happens, but maybe that’s me being too optimistic.

In any case, “The Answer” is an interesting piece that makes you contemplate your place in the universe while also interrogating what lengths you’re willing to go to to stop authoritarians from undermining our democracies. Indeed, it’s a rather interesting companion piece to “Ozymandias” in that it asks us to examine whether or not or societal pursuits really are as important as our leaders claim they are as the dying days of empire draw ever closer, whereas Shelley is examining how futile absolutist ambitions seem long after the monarchs of old are dead and gone.

The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats

Artist credit: “The Sphinx of the Seashore” by Elihu Vedder

Despite World War I having ended the previous year, all was not well in the state of Ireland in 1919. The Irish War of Independence had commenced that January, and the Great Influenza Epidemic had spread to the Emerald Isle, which is estimated to have caused 25,000 excess deaths. One of those infected was none other than W.B. Yeats’ pregnant wife, Georgie, which was terrifying for Ireland’s greatest poet, as the virus had a 70% mortality rate for pregnant women. Luckily, Georgie recovered and gave birth to a healthy baby girl. Still, Yeats had more than enough cause to write one of the most haunting poems of the early 20th-century modernist movement.

In contrast to the somewhat hopeful vision of societal collapse that Jeffers presented in “The Answer,” Yeats portrays a more cynical, almost Lovecraftian, outlook that seems to foreshadow an oncoming Kali Yuga-type age where “things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world. The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned.” The narrator looks toward the Levant, hoping that Jesus Christ’s Second Coming will rescue humanity from its downward spiral. Instead of the Nazarene’s kind face, however, the narrator is confronted by “a shape with lion body and head of man, a gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,” surrounded by carrion birds as it “slouches towards Bethlehem to be born.”

To understand what Yeats was trying to say with this poem, one needs to understand his theory of “gyres,” as referenced in the opening lines (“Turning and turning in the widening gyre, the falcon cannot hear the falconer.”). Yeats believed that human history progressed in a series of 2,000-year epochs, punctuated by significant events such as the birth of Jesus or the Trojan War. He believed that World War I marked the end of the gyre that had started with Christ’s birth, and that the new gyre was the beginning of an age of chaos and strife. This is symbolized by the rough beast slouching toward Bethlehem, which resembles a creature from pagan myths, such as the sphinx or manticore, more than the glorious return of Christ prophesied in the Book of Revelation.

It might be easy for people who share my leftist beliefs to scoff at such doomsaying, especially when you consider that Yeats’ politics were fiercely anti-democratic and borderline fascist. Still, looking back on the century that has passed since “The Second Coming” was published, it’s hard not to agree that something seems to have gone very wrong with the world since the outbreak of World War I, which appears no closer to being solved now than it was back then. I would argue that imperialist capitalism is the cause of all this, rather than a mob unleashed by the fall of the divine right of kings, like Yeats seemed to believe. That’s just me, though. What do you think?

To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time by Robert Herrick

This poem is most famous for its inclusion in the classic 1989 film Dead Poets Society, where the late great Robin Williams’ character, John Keating, uses it as an aid for teaching his students about the concept of carpe diem (“seize the day” in Latin). However, I was first exposed to it by one of my favorite songs: “A Change of Seasons” by Dream Theater. This progressive metal epic, told in seven movements over 23 minutes, tells of drummer Mike Portnoy’s struggles with addiction and losing his mother in a plane crash. Most importantly for the purposes of this essay, though, the third movement, appropriately titled “Carpe Diem,” includes audio samples from Dead Poets Society, including Williams reading the first stanza of “To the Virgins…”

The basic message of the poem, composed in 1648 for Herrick’s verse collection Hesperidies, is to the women of Herrick’s age. He urges them to take advantage of their beauty while they are still young, lest they lose their chance at a husband while they are still in their prime. He compares their aging to the rising sun, for, paradoxically, the higher it is in the sky, the closer it’s getting to setting and leaving the world in darkness through the night.

Contemporary feminist critics may take issue with the message that the best way a young woman can seize the day is to find a young man to marry, especially those of a more sapphic persuasion. Still, though, the fact that the poem is still being taught as a shining example of carpe diem in literary form shows that there are relevant messages to be gleaned from it even in a post-women’s liberation age. Whether or not one is male, female, or somewhere in between, time flies quickly for us all, and it’s easy for us to waste it if we’re not paying attention. John Keating’s male students sure seemed to think so.

I feel like I’ve been wasting time these last few years myself. I’m caught in a space where I’m comfortable in my routines, but still not happy with my situation because I’m stuck living with parents who hold political views that I find out of touch at best and downright morally repugnant at worst. I keep telling myself I’m going to ask them to sign me up for a driver’s course one of these days, but then I worry that if I’m ever honest about how far to the left my politics have drifted over the years, they might become convinced that I’m too crazy to be trusted to go out into the world on my own and won’t let me leave. Maybe I’m being too overblown and ridiculous about it, though. I’ve still got all summer to gather the courage, so we’ll see about that.

Nothing Gold Can Stay by Robert Frost

Artist credit: Zahuranecs on DeviantArt

I was first introduced to this much more bittersweet take on the passage of time by the classic novel The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton, as well as its equally classic film adaptation by Francis Ford Coppola. I recall the novel being one of the few books introduced to us by our middle and high school English teachers that most students in my grade agreed was something they enjoyed. Indeed, it was probably my introduction to Robert Frost in general. While I’m sure there are differences between the rural St. Lawrence River Valley where I grew up and the New England farms and forests that Frost wrote about, it’s safe to say that a lot of the imagery encountered in his work is resonant for anyone who lives in the northeastern United States.

This poem deals with much more abstract concepts than “The Road Not Taken” and “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening,” albeit with equally vivid natural imagery. With just a single eight-line stanza, Frost demonstrates the fleeting and ephemeral nature of all that is beautiful about the world, using the famous autumn leaves of New England’s deciduous forests as a metaphor. It’s easy to read a cynical message from the poem, including when Frost describes golden autumn leaves as nature’s “hardest hue to hold” and the almost theatrically depressing line, “And Eden sank down to grief.” However, Frost also hints at a cyclical nature to the death of beauty. For instance, the penultimate line reads, “So dawn goes down to day,” indicating that there is a bright future ahead even if things seem dark and depressing now.

Indeed, it’s hard not to expand this concept to the idea of golden ages and how fleeting they often are when you look back across the vast expanses of history. From Pax Romana and the Islamic Golden Age to the various golden ages ascribed to different phases of the ancient Egyptian, Chinese, and Indian dynasties, they all seem to last only a few centuries at most. As I mentioned earlier, I believe that the United States that our Founding Fathers envisioned is rapidly approaching the end of its natural lifespan, and that Trump and the Department of Government “Efficiency” are only hastening the inevitable. The final collapse of the America that we all grew up in is almost certain to be painful as Eden sinks to grief, but I choose to believe that we can form a more just and egalitarian social system in its place and leave the neoliberal hellscape that Reagan and Thatcher forced upon us in the dustbin of history where it belongs. So dawn goes down to day…

Troll by Shane Koyczan

Still from an animated YouTube video made to accompany the poem (linked above)

Now we move from poems about existential terrors from the natural world and the passage of time to a poem about an existential terror entirely of our own making: the Internet.

Shane Koyczan is a Canadian poet known for his poetry that explores dark subject matter, including bullying, mental health issues, and the challenges of high school. His most famous poem is undoubtedly “To This Day,” an autobiographical work exploring bullying and the psychological scars it leaves. However, the poem of his that I chose for the anthology explores what happened after the Internet gave the bullies the freedom and anonymity to unleash their worst impulses upon an unsuspecting public.

Koyczan directly compares the trolls of the online world to the trolls of Norse mythology and fairy tales like “The Three Billy Goats Gruff” that dwelt under bridges waiting for a meal, noting ominously that “while the world above you invented the wheel, you stayed put, knowing it would one day need to roll over top of you to get where it’s going.” Koyczan then proceeds to describe in excruciating detail what happened when the modern world reached the trolls and they, in his words, “migrated from living underneath bridges to living under information super-highways.”

The World Wide Web gave the trolls and the cyberbullies the ability to extend their cruelty far beyond the schoolyards and secluded mountain valleys that used to be the limits of their domain, allowing them to harass people they had never and would never meet in person, even on the complete opposite side of the globe. They would become more fearsome than the monsters in children’s storybooks, with parents helpless to stop them as the computer and smartphone gave them much easier access to their vulnerable youngsters (“We turned ourselves into life preservers, hoping to save as many as we could. But the fathers who stood guarding closet doors and the mothers who secured the floors underneath beds all shook their heads, not knowing how to deal with you.”). Their reign of terror would become all the more terrible the more the Internet became inextricable from daily life, with the most mentally and emotionally fragile among us bearing the deadly consequences (“You’ve talked strangers to death and laughed, and as each family learns to graft skin over the wounds you gave them, you hem yourselves into the scar. You have coaxed the sober back into bars; handed out cigars at memorials; offered nooses, cliffs, and pills to those who unfortunately found you before they found help.”).

Reading this now in 2025, for all the borderline Lovecraftian language Koyczan uses to describe the threat that cyberbullies pose, it almost feels like he’s underselling just how dangerous trolls really are, especially since, as one commentor on the YouTube video I linked above pointed out, “we just elected the most dangerous troll into public office.” And it’s not just Trump; Elon Musk, who Trump hired to take a wrecking ball to essential government services under the pretense of making it more “efficient,” has dubbed himself the “Chief Troll,” something he’s demonstrated by literally giving a Nazi salute at Trump’s second inaguration. Musk insists that it was just a joke, but I’m sure Koyczan would agree that “it’s not cute. It’s not funny.”

I should probably mention that this poem is also significant because of who first introduced it to me: Jonathan Rozanski, better known on YouTube as The Mysterious Mr. Enter. Mr. Enter is best known for series like “Animated Atrocities” and “Admirable Animations,” in which he reviews animations that he dislikes and likes, respectively. It was through one of these “Admirable” videos that I was exposed to “Troll” and Shane Koyczan’s work as a whole. Enter was controversial in his heyday for his emotional and often vitriolic style of review, which got on a lot of people’s nerves. What attracted me to him, though, was that he was on the autism spectrum, just like me, and openly spoke about his struggles with the disorder, which was something I greatly appreciated.

As the first Trump administration wore on, however, I began to grow more alienated from Mr. Enter as he started to inject more politics into his videos, which was a problem as he seemed to lean more and more to the right, whereas I was drifting more and more to the left. I gave up on him entirely during the COVID pandemic when he started making videos where he argued that healthcare isn’t a human right and that the measures governments were taking to show the spread of the virus were violations of human liberties. While he luckily seemed to avoid turning into a full-on anti-woke crusader (and has since apologized for how horrible of a person he became during the pandemic), he’s still had enough controversies that have convinced me that it’s probably best to leave him in the past, like when he was widely mocked on Twitter over a bizarre take that Pixar’s Turning Red didn’t talk enough about 9/11.

Mr. Enter when The Emperor’s New Groove doesn’t end with Francisco Pizarro sweeping in and killing everyone.

Getting back to the subject at hand, however, as bad as the cyberbullying situation may have looked to Koyczan back when he first published “Troll” in 2014 (and it was pretty bad; this was the year that Gamergate happened, after all), I don’t think he could have predicted that the situation would get so bad that the trolls would be literally running the most powerful government in the developed world. Still, I think it remains just as true now as it was then that the best way to deal with the trolls is not to validate their low expectations of us and to bring out the best in the rest of humanity to prove them wrong. Or, as Koyczan puts it, “now armed only with resolve, we can no longer afford to tell ourselves you aren’t real. We will not let you make your dinners out of the things we feel.”

Remember by Joy Harjo

Cover for the storybook adaptation of the poem, published on March 21, 2023 by National Geographic Books

This is probably my favorite poem from the anthology. When the professor asked us to choose one poem from our respective collections to read aloud to the rest of the class, this was the one I chose. Indeed, that poetry class was where I was first introduced to Joy Harjo, as her collection In Mad Love and War was one of our textbooks for the class (I still have my copy on my bookshelf). Looking back now, In Mad Love… might even have been the genesis point for my ongoing fascination with Native American culture, something that was fueled by my decaying faith in American society and wondering whether or not we may have thrown the baby out with the bath water when we forced our Indigenous neighbors to follow the white man’s path at gunpoint.

In a lot of ways, “Remember” could be read as Harjo boiling down all Indigenous faiths down to their animistic core. True, the details of Aboriginal spiritual beliefs vary widely among different tribes (the Haudenosaunee creation myth is very different from the Navajo creation myth, for example), but nearly all of them share an intense spiritual connection with the land and its non-human inhabitants, with the animals regarded as their brothers and sisters (“Remember the plants, trees, animal life who all have their tribes, their families, their histories, too. Talk to them. Listen to them. They are alive poems.”). This spiritual connection also extends to the community they are brought up in, whether it be one’s immediate family (“Remember your birth, how your mother struggled to give you form and breath. You are evidence of her life, and her mother’s, and hers.”), or the universe as a whole (“Remember the sky that you were born under. Know each of the stars’ stories.”).

Of course, some of the more modern sentiments Harjo adds in here and there don’t hurt, like the paens to racial unity (“Remember the earth whose skin you are: red earth, black earth, yellow earth, white earth, brown earth, we are earth.”) or the nods to pantheism, which fits with Indignous reverence of nature (“Remember you are all people and all people are you.

Remember you are this universe and this universe is you.”). It’s all in service of the main message: no one person is an island. We are all part of a community, both that of our human neighbors and family members and of the ecosystems that many of us humans vainly try to convince ourselves we have no connection to. We must listen to what they have to teach us if we want to flourish in our short lives on Earth.

It’s a lesson many in the younger generations seem to be taking to heart as the pressures on our environment from capitalist exploitation become ever more apparent. Hopefully, enough of them listen to the living poems composed by the plant and animal tribes that live just outside our doors before it’s too late.

Christmas Bells by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Christmas isn’t always the most wonderful time of the year, especially during times of war. This was certainly true for the celebrated poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow on Christmas Day, 1863, as he was still reeling from the news that his son, Charles Appleton, had been wounded in the Battle of Mine Run (something that occurred after he joined the Union Army against his father’s wishes). This undoubtedly added to the depression Longfellow had been feeling in the two years since his wife, Frances, had died in a freak accident involving a burning dress. As such, Longfellow would spend that Christmas writing a poem that would one day join A Christmas Carol and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” as a certifiable holiday classic.

“Christmas Bells,” presented as a collection of seven stanzas in limerick form, starts optimistically for the first three stanzas, with the narrator listening to the church bells and carol-singing choirs and reveling in the “chant sublime of peace on Earth, goodwill to men!” But then the poem takes a dark turn in the next three stanzas when the Civil War commences, as the carols are drowned out as “the cannon thundered in the South… as if an earthquake rent the hearthstones of a continent.” The narrator hangs his head in despair as the war rages on and the holy songs of peace on Earth and goodwill to men are drowned out in the chaos. But then comes the last stanza, which acts as a plea for the audience not to give up on the prospect of peace:

Then pealed the bells more loud and deep:

"God is not dead, nor doth He sleep;

The Wrong shall fail,

The Right prevail,

With peace on earth, good-will to men."

This final stanza may ring hollow for some nowadays, given the numerous social issues plaguing the Earth (climate change, the rise of fascism, economic inequality, systemic racism, etc.). Indeed, this poem feels particularly depressing to me, given the context in which I first heard it as a kid. The poem was used as the theme for a Christmas Eve pageant at my local church, in which my father dressed as the Grim Reaper, read a list of the number of deaths caused by wars America was involved in, and recited the quote, “Hate is strong and mocks the song of peace on Earth, goodwill to men.” Those words coming out of his mouth feel like a cruel joke nowadays, given his staunch support of Israel (even as the bodies of Gaza’s children keep piling up) and for Agent Orange (even as he gets more nakedly racist by the day).

But there’s always a cause for hope if you look hard enough. Whether it’s the widespread protests against the Gaza genocide and those who support it, or against Trump’s blatant power grabs, there’s always a group of people brave enough to take to the streets to do what they can to hinder the forward march of authoritarian hatred as far as they are able. Even Longfellow managed to find a glimmer of hope in the situation that spawned this poem when Charles recovered from his wounds and returned to his father’s side. It certainly didn’t hurt that the staunchly abolitionist Longfellow lived to see the end of the war and the abolition of slavery in the United States.

Perhaps the best lesson to take from “Christmas Bells” is something similar to the classic Martin Luther King quote that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” However, if history teaches us anything, it doesn’t bend toward justice on its own; it bends when the silent majority gains the courage to put their collective thumbs on the scale.

There Will Come Soft Rains by Sara Teasdale

Like many other high school English students, I was first exposed to this poem by the chilling short story of the same name by the legendary science fiction writer Ray Bradbury. It tells the story of a house full of automated systems that carries on with its programming even after the family it serves has been wiped out by a nuclear holocaust, with shadows of the vaporized residents etched into the outside walls being the only trace left of their existence. The house robots continue as if nothing happened until the building burns down due to a freak accident caused by a windstorm, with only a wall endlessly repeating the date and time left standing. The connection to the poem comes when one of the robots recites the poem in full for the deceased mother of the household.

Both Bradbury and Teasdale wrote in the context of potentially world-ending disasters looming over them. Teasdale wrote the poem in 1918 amid the Great Influenza Epidemic and the German Spring Offensive, which was the last-ditch attempt by the German army to win World War I by any means necessary (it failed, miserably). Bradbury wrote the short story in 1950 in the early years of the Cold War, with nuclear weapons hanging like the Sword of Damocles in the collective unconscious. It’s probably no surprise that the two were contemplating the end of all humanity in times like those.

It is interesting how both the poem and the short story seem to occupy opposite sides of the idealism vs. cynicism spectrum. Teasdale imagines a world where nature remains in harmony (birds sweetly singing, frogs croaking contentedly, etc.) that scarcely remembers that humanity even existed. Bradbury, on the other hand, imagines a world turned into a burned-out shell of its former self, with the scars of humanity’s last destructive act permanently seared into the Earth’s surface. It makes sense, considering how monumentally destructive nuclear war would be if it happened in real life.

Either way, both works serve as a good wake-up call for some of the more chauvinistic individuals out there who have grand visions of us being somehow superior to all of the other creatures in the great chain of being. We’re just as vulnerable to going extinct as the dinosaurs, mammoths, and dodos of yesteryear. The problem is that it is things of our own creation that have the potential to do us in, and probably a whole host of other species in the process.

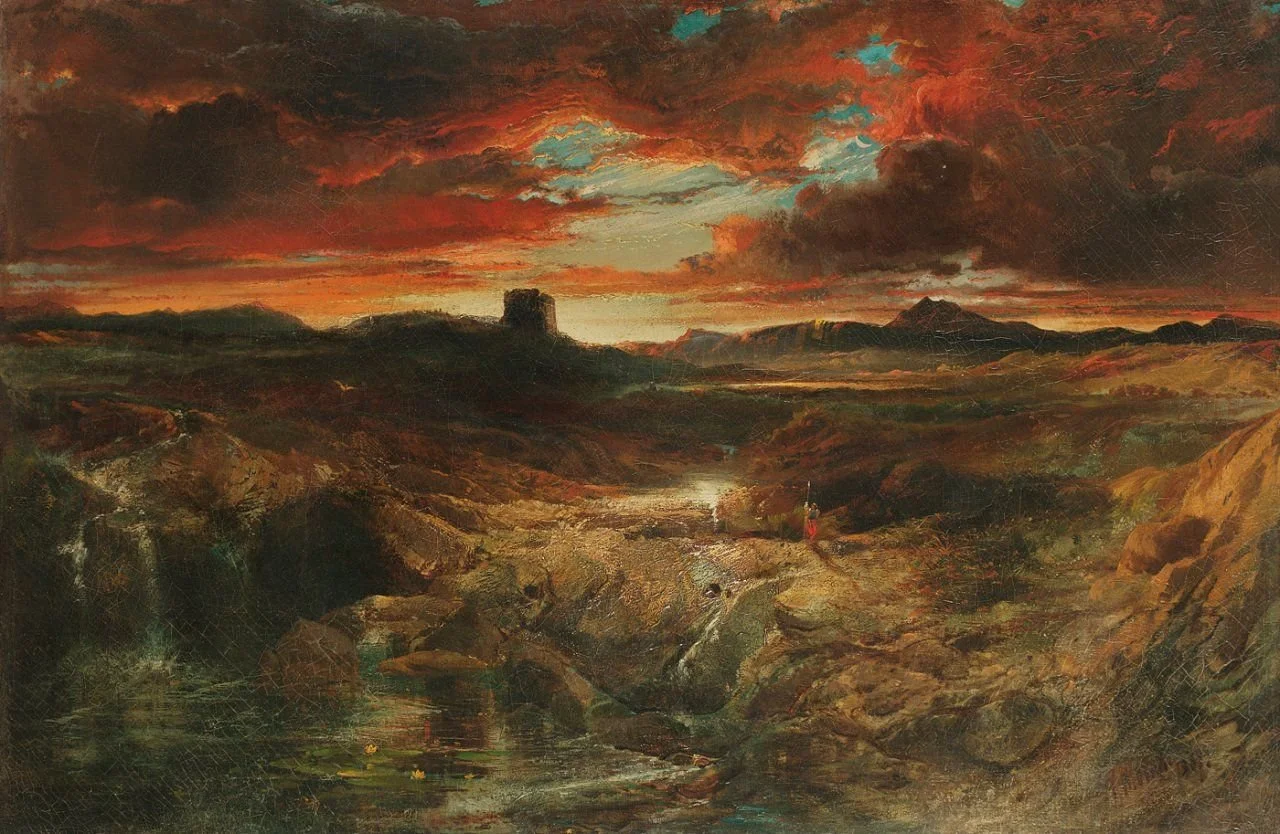

Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came by Robert Browning

Artist credit: Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came, painted by Thomas Moran in 1859.

Longtime readers of my blog will know that I have a bit of a history with The Dark Tower series of novels by Stephen King. You can probably guess that the anthology assignment came along right when I was in the middle of working my way through the books, so naturally, I decided to include one of the works that inspired King to write the books in the first place: an epic poem written in 1852 by one of the most prominent figureheads of Victorian poetry. It was inspired by the 11th-century epic poem The Song of Roland (whose central protagonist is basically to Emperor Charlemagne what Sir Lancelot was to King Arthur) and an offhand reference in Shakespeare’s King Lear in which a character tries to present himself as insane.

It’s rather astonishing how closely the imagery depicted in the poem matches that of Roland Deschain’s Mid-World even back then. Childe Roland, the narrator and protagonist of the poem, describes in gruesome detail the dessicated wastelands he wanders through in his quest to reach the Dark Tower, including featureless wastelands populated only by carrion birds and mummified horses, a fearsome river that he believes has dead bodies for stepping stones, and a vast plain that he imagines was the site of an ancient battle that the land still hasn’t recovered from. It doesn’t help that the landscapes keep shifting in front of his eyes, possibly indicating that these horrible visions are due to Childe Roland’s fracturing sanity. Despite his cynicism and exhaustion, Childe Roland continues his quest until he discovers the Dark Tower hidden inside a mountain range. As ghosts of his friends and travel companions appear in a sheet of flame, an overjoyed Roland signals his arrival at the tower by blowing on a slug-horn. The poem ends there, leaving what Roland finds inside the tower a mystery.

Of course, there are notable differences between the poem and King’s story. The former plays almost like a cynical mockery of the hero’s journey, portraying the journey as an endeavour so hopeless that Childe Roland can’t bother to muster any enthusiasm when a crippled old man shows him the path to the tower at the beginning. The constant meditations on decay, futility, and isolation make his journey feel more like the Dark Tower is a symbol of death waiting for him at the end of his journey. Even when Childe Roland does finally reach his goal, there is no celebration or sense that anything concrete has been accomplished (something that isn’t helped by the fact that, as mentioned above, the very title of the poem comes from a Shakespeare character just making stuff up to make himself look insane). Roland Deschain, on the other hand, has a clear goal in mind, which is to stop Randall Flagg and the Crimson King from using or destroying the tower for their own nefarious ends while also learning the secret to saving his dying world in the process, which makes it more of a standard fantasy narrative (albeit with a distinctly Stephen King twist).

Despite such an outwardly cynical presentation, though, I think a glimmer of hope can still be extracted from the end. While Childe Roland’s quest clearly has no cosmic significance and is unlikely to be remembered for it, he still feels like it was all worth it in the end. The phantoms of his long-dead friends that appear as if to congratulate him seem to confirm this, even if it is just a hallucination. Perhaps that’s the message Browning was trying to get across; that no matter how difficult the journey to accomplish your dreams may be, it’s worth psuhing through it to the end.

And that’s all I have to say about my favorite poems. That was a fun little detour from the usual subjects I tend to cover on this blog. Still, I think it’s time for me to get back to business as usual. I can’t say for sure what the next blog post will be. My left brain is telling me that I should get back to work on the Jurassic World Dominion review and finally get the retrospective back on track. My right brain is telling me that it would be much more fun to write about Pennsylvania cryptids as the next entry in “Cryptids of North America.” Still another part of me has noted that I haven’t done an episode of P.J.’s Ultimate Playlist in a while.

Whatever I decide to do next, I promise I will see you all again very, very soon. Y’all come back now! Ya hear?