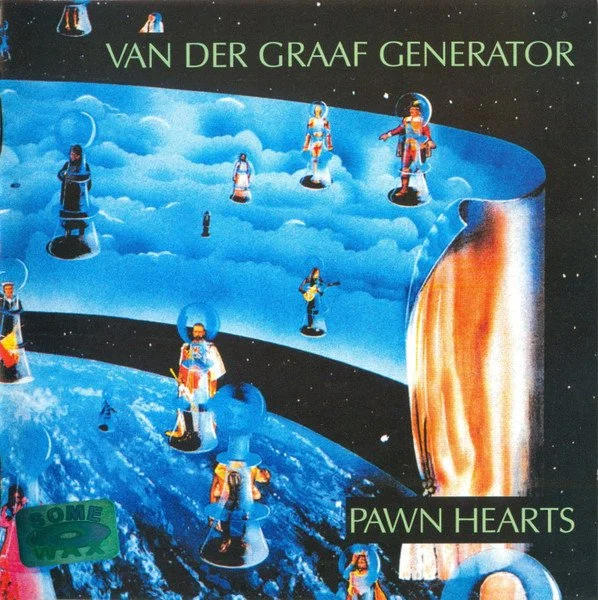

P.J.’s Ultimate Playlist #9: “Lemmings” by Van der Graaf Generator

The album cover for Pawn Hearts, of which “Lemmings” serves as the opening track

Progressive rock has gained a reputation over the years (perhaps fairly, perhaps not) as the red-headed stepchild of rock and roll, with many critics deriding its attempts to introduce the artistic sophistication of classical and jazz music into the genre as missing the point of rock entirely. The economic troubles of the 1970s didn’t help matters, as many prog rockers’ lyrical themes of fantasy and idealism came to be viewed as unrelatable compared to punk rock’s stripped-down simplicity and angry, often political lyrics. Most of the prog rock bands that survived either matched punk’s cynical outlook (like Pink Floyd or King Crimson) or had a harder-rocking sound that could compete more easily (like Rush, Styx, or Queen).

But I’m not here to talk about any of those bands today. Instead, I’m more interested in highlighting one of the weirder bands to come out of the early 70s prog rock renaissance, one that is definitely much more obscure than the others I’ve mentioned, but has gained a reputation as being one of those “your favorite musician’s favorite musician” type of artists. So, without any further ado, allow me to introduce you to Van Der Graaf Generator.

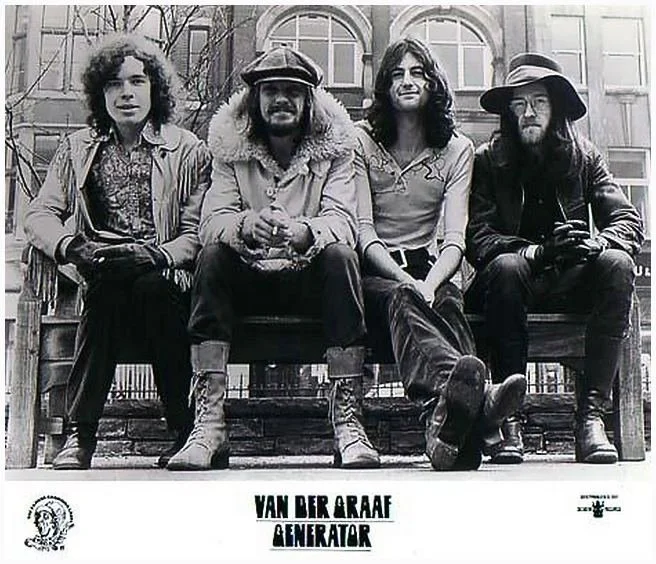

The Artist

From left to right: Hugh Banton (keyboards, bass), Guy Evans (drums), Peter Hammill (lead vocals, guitars, keyboards), David Jackson (brass and woodwind instruments)

Van der Graaf started innocently enough with the psychedelic folk record The Aerosol Grey Machine in September 1969, which was apparently intended as a solo album for lead vocalist Peter Hammill until contractual obligations forced him to release it under the band name. But then the band quickly forged its own original sound on its following two albums, The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other (February 1970) and H to He, Who Am the Only One (December 1970), which centered on David Jackson’s twin saxophones and Hugh Banton’s electric organ, with little to no electric guitars to speak of.

Now, I imagine you would think music with that kind of instrumental lineup would sound like smooth jazz, right? It surely wouldn’t produce music so evil and terrifying that it could give Black Sabbath a run for their money, right? Actually, no, because Peter Hammill somehow took that combination of musicians and managed to churn out some of the most nightmarish music to come out of the early ‘70s. Banton wove ominous drones with his organ, Guy Evans pounded out frenetic rhythms on his drumset, Jackson made his twin saxs’ screech and wail like banshees, and Hammill would utilize his startlingly wide vocal range to switch from smooth whispers to shrieking high notes without warning.

All of this made for a uniquely harrowing listening experience and probably the heaviest band from that era that wasn’t a proto-metal act. Indeed, compare the title track of Black Sabbath to the last two minutes of “White Hammer” from …Wave to Each Other, and then marvel at how VDGG managed to achieve a sound as crushing as any Tony Iommi riff without electric guitars (incidentally, both albums were released within weeks of each other). The dark subject matter that Hammill liked to talk about in his lyrics didn’t help, from the witch trials of medieval Europe (“White Hammer”) and apocalyptic natural disasters (“After the Flood”) to ravenous man-eating sharks (“Killer”) and suicidally insane lighthouse keepers (“A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers”).

Naturally, such a formula didn’t readily make them a mainstream success (except in Italy, for some reason). However, a diverse array of musicians in the decades since have cited VDGG as an influence. Their most surprising fan is probably Sex Pistols frontman Johnny Rotten (or John Lydon offstage), whose professed love of prog bands like VDGG, Magma, and Can caused tension between him and his manager, Malcolm McLaren. Other musicians who have named VDGG as an influence include Geddy Lee of Rush, Julian Cope of The Teardrop Explodes, Graham Coxon of Blur, Philip Oakey of the Human League, Mikael Akerfelt of Opeth, Marc Almond of Soft Cell, Fish of Marillion, and Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden.

Of course, as Lydon notes in this interview, recommendations for any of VDGG’s work (or anything involving Peter Hammill, for that matter) are a bit difficult, as the band is so far outside of what one expects from a rock band that it’s bound to scare a lot of people away. Still, as New Order drummer Stephen Morris notes in this Guardian article, the people who do like Peter Hammill really like him for how honest and raw his music is compared to so many other prog rockers, almost to the point that it can be painful to listen to at times. Much as I adore the more conventional prog bands like Yes, Genesis, or ELP, they definitely don’t produce the same visceral emotions as a Van der Graaf track.

Is any of this making sense? Perhaps the best way to demonstrate what I mean is to home in on one specific song and help break it down to see what makes it and its songwriter tick. As I’m sure you’ve gathered from the title, that song will be “Lemmings,” the opening track of the band’s fourth album, Pawn Hearts, considered by many fans to be VDGG’s magnum opus (others swear by the band’s 1975 comeback album, Godbluff). It tells a tale of a person looking out over a society seemingly hellbent on committing metaphorical mass suicide and struggling to find hope that he will ever dissuade them from their self-destructive course.

So let’s talk about it.

The Song

Taxidermied Norway lemming (Lemmus lemmus)

By Argus fin - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=832566

As is probably obvious from the title, “Lemmings” uses the common urban legend that these tiny, hamsterlike tundra dwellers commonly throw themselves off cliffs en masse for no apparent reason. This has led to the term “lemming” being widely used as a pejorative for those who mindlessly follow the crowd, even when that crowd is clearly leading them to certain destruction. I could go on a tangent on how that stereotype is based on misunderstandings of observed lemming behavior and fueled by an abusive Disney documentarian, but that’s not exactly relevant to the subject matter of the song, so we’re just going to move on.

The song, much like VDGG’s recording career, starts deceptively calm with a gentle acoustic guitar riff fading in, while Hammill sets the scene with an equally calm vocal delivery:

I stood alone upon the highest clifftop;

Looked down, around, and all that I could see

Were those that I would dearly love to share with

Crashing on quite blindly toward the sea.

The tone quickly begins to shift as Banton, Evans, and Jackson join in on their instruments and Hammill switches to a more strident voice for the last three lines of the first verse:

I tried to ask what game this was,

But knew I would not play it.

The voice, as one, as no one, came to me:

We then spend the next four verses hearing from the lemmings themselves, as they explain their motives for this seemingly pointless death march. First, they pin the blame on society’s leaders:

“We have looked upon the heroes

And they are found wanting.

We have looked hard across the land

But we can see no dawn.

We have now dared to sear the sky

But we are still bleeding.

We are drawing near to the cliffs.

Now we can hear the call!

They outline the apocalyptic state of the world and the nihilistic meaninglessness that seems to permeate every aspect of modern society, and conclude that death is the only possible escape:

“The clouds are piled in mountain shapes.

There is no escape except to go forward!

Don’t ask us for an answer now;

It’s far too late to bow to that convention!

What course is there left but to die?

The music slows down for a short time, seemingly representing Hammill contemplating what the lemmings have just told him, before the main saxophone riff strikes up again as the lemmings continue their rant:

“We have looked upon the high kings;

Found them less than mortals.

Their names are dust before the just

March of our young, new law.

Minds stumbling strong, we hurtle on

Inot the dark portal!

No one can halt our final vault

Into the unknown maw!

Despite the pain they admit to causing their elders and loved ones, the lemmings insist that the sky has become so polluted that death is inevitable anyway. While they admit they don’t know what’s waiting for them in the next world, anything has to be better than the hell on earth they’re currently living in:

“And as the elders beat their brows,

They know it’s really far to late now to stop us,

For if the sky is seeded death,

What is the point in catching breath? Expel it!

What cause is there left but to die

In search of something we’re really not to sure of?”

The POV then switches back to the narrator as Hammill repeats the last line three times as if in contemplation and then says, “I really don’t know why.” Another short instrumental break follows that is equally gentle and contemplative, before roaring back to full volume as Hammill provides his answer to the lemmings’ fatalistic question:

I know our ends may be soon,

But why do you make them sooner?

Time may finally prove

Only the living move her,

And no life lies in the quicksand!

Another instrumental break follows, punctuated by screams from Hammill that sound remarkably similar to the kind of screams that Rob Halford would deploy a few years later while helping Judas Priest lay the foundations of classic heavy metal. As the screams fade, the music slows down again, only to be interrupted by an explosion of noise about five minutes in that transitions into the song’s second movement, “Cog.” There, Hammill takes some time to empathize with the lemmings’ plight, describing the way modern society has mistreated them using some startlingly nightmarish imagery:

Yes, I know, it’s out of control! Out of control!

Greasy machinery slides on the rails;

Young minds and bodies on steel spokes impaled!

Cogs tearing bones! Cogs tearing bones!

Iron-throated monsters are forcing the screams;

Mind and machinery box press our dreams!

But then Hammill rebukes the lemmings with a simple five-word phrase:

But there is still time…

From there, the song transitions back into a reprise of the saxophone riff as Hammill offers a message of hope to the lemmings:

Cowards are they, who run today!

The fight is beginning!

No war with knives! Fight with our lives!

Lemmings can teach nothing!

Death offers no hope! We must grope

For the unknown answer!

Unite our blood! Abate the flood!

Avert the disaster!

He points out that surrendering to suicidal nihilism does nothing to solve society’s problems and that they are merely playing into the hands of the uncaring ruling class by further destabilizing the world order. He also pleads with the lemmings that there are still beautiful things in this world worth fighting for:

There’s other ways than screaming in the mob;

That merely makes us cogs of hatred!

Look to the why and where we are!

Look to yourselves and to the stars,

And in the end,

Finally, Hammill makes probably his most poigniant plea yet to the lemmings: If not for yourselves, then live for your children and your children’s children, because even if you don’t manage to achieve a better world in your lifetime, maybe they will:

What choice is there left but to live

In the hope of saving our children’s children’s little ones?

What choice is there left but to live?

What choice is there left but to live?

What choice is there left but to live to save the little ones?

What choice is there left but to try?

What choice is there left but to try?

What choice is there left but to try?

From there, the song spends its last two minutes as a quiet and contemplative instrumental, with Jackson trading his saxophones for a flute and Evans sticking to light tapping on the cymbals, before finally ending around 11 1/2 minutes after it began with a final crack on the snare from Evans.

Personal Thoughts

You guys probably know full well why this song resonates with me. I’ve made no secret of my own fears of a coming apocalypse brought on by uncaring billionaires and their politician allies. “Lemmings” takes a different approach than attacking them directly, however. Instead, it turns its ire on those of the working class who are either so caught up in nihilism and depression that they think “We’re doomed anyway, so what’s the point of doing anything?” or so convinced that we have it good under capitalism that they’ll side with the uncaring ruling class, even though doing will almost certainly lead to disaster.

Today, outlooks like this are commonly referred to as “doomerism.” It’s certainly not hard to see where they’re coming from. Everything since 2008 has felt like a downward spiral of economic instability, environmental collapse, and political polarization that prevents us from fixing the worst problems facing our society. The worst effects of climate change feel more and more inescapable these days, numerous minorities (trans people, immigrants, autistic people like myself, etc.) increasingly feel like they have a target on their backs, and the ongoing investigations into the pedophilic billionaire sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein reveal just how disgustingly perverse our ruling class truly is.

Of course, things probably felt equally bad in 1971 when Peter Hamill wrote “Lemmings.” The sunny optimism of the 60s, symbolized by Woodstock, the American civil rights movement, and the counterculture movement, had been shattered by tragedies like the Manson family murders, the disastrous Altamont Free Concert, and the assassinations of civil rights leaders like Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. The war in Vietnam showed no signs of slowing down, and the Nixon administration had begun a backlash against the victories of the civil rights movement that would spell disaster for the United States in the form of the War on Drugs and the rise of the new hypercapitalist neoliberal order that we are still suffering under today.

Still, “Lemmings” is open enough in its wording that its lyrics can apply equally well to the social problems over half a century later. For instance, the lyric “We have now dared to sear the sky, but we are still bleeding” is clearly a reference to the fear of nuclear armageddon, yet it can be just as deftly applied to the worsening effects of anthropogenic climate change. The lyric “We have looked upon our heroes, and they are found wanting” can easily describe my feelings toward my country’s founding fathers, who are often held up as godlike figures who created the greatest bastion of human freedom the world has ever known, but in reality were ruthless slave drivers who slaughtered North America’s indigenous inhabitants to fulfill their greedy ambitions. The same could be said for my country’s current leadership, who some (like my parents) continue to hold up as saviors despite how openly they wear their chauvinism and childish vindictiveness on their sleeves (“We have looked upon the high kings, and found them less than mortals”).

But despite the dystopian bleakness of the lyrics, Hammill still seeks to remind us that “there is still time,” a sentiment that remains just as true in 2026 as it was in 1971. Yes, the Trump administration seems dangerously close to turning the United States into a Christofascist hellscape and dragging down the rest of the free world with it. But the heavy-handed tactics of ICE (which have led to the completely unnecessary and avoidable deaths of Keith Porter, Renee Good, and Alex Pretti) and Trump’s increasingly pathetic attempts to convince us that he never had anything to do with Jeffrey Epstein have led to a massive wave of protests that have revealed that their grip on power isn’t nearly as ironclad as they want us to believe. They can scream at us until they’re red in the face that the protesters aren’t real Americans and that they’re only being paid to be there by George Soros or some other stand-in for “international Jewry,” as they might put it, but that doesn’t change the fact that Trump’s popularity is at record lows, and America is getting fed up.

And even if things like America’s descent into fascism and climate apocalypse are predestined, so what? Does that mean we just roll over and let it happen? I don’t think so. Because, as one Peter Joseph Andrew Hammill once said, “What choice is there left but to live to save our children’s children’s little ones?”

Well, this one series I haven’t dusted off in a while. It was fun to get back to talking about some of my favorite music again, and I’ve already got some more new ideas for other “Playlist” episodes. There’s an old Bob Dylan tune I’ve been thinking of talking about, and I’ve also compiled a list similar to the one I did for Led Zeppelin, ranking the songs of another seminal classic rock act. I won’t reveal who it is yet, as I’ve still got a lot of other stuff I need to take care of before I get to that article. Still, I think it will lend me some material equally as good as the Zeppelin article.

Speaking of “other stuff I need to take care of,” tune in next time when I finally take care of my “best animated series of 2024” list. It might take a while for that one to come out, but I promise it will be well worth the wait when it does. Until then, stay safe, remember that there is still time, and I’ll see you all very soon, I hope.