My Favorite Animated Films of 2024

So…this took way longer to come out than I expected.

There are several reasons for this that I outlined in my recent New Year’s update (mental health struggles, getting distracted by other projects, the looming shadow of the Jurassic Park retrospective). I was pretty optimistic about the list earlier in the year, since, unlike with the 2023 films, I had already seen all of the Academy Award nominees for Best Animated Feature (well, except for Inside Out 2, for reasons I’ll get into in a bit). I was even going to bend my personal rules a little bit and save some foreign features, like The Glassworker, for the 2025 list once they received an American release. Sadly, though, it seemed like the universe was conspiring against me this year, so we had to wait until 2026 to get my “best of 2024” lists. Still, better late than never, right?

Before we get started, though, let’s set some ground rules. First, I’m not going to do that thing I did in the last movie list, where I dedicated a section to “dishonorable mentions,” or films that I found to be a disappointment. I did that for the second 2023 list for Disney’s Wish, but for this one, I think I’d rather accentuate the positive for the most part.

This isn’t to say that there weren’t any disappointments for me in the 2024 animated film sphere. For instance, Saving Bikini Bottom: The Sandy Cheeks Movie was a massive letdown for this SpongeBob fan, with characters exaggerated to the point of being parodies of themselves, plotlines being dropped and not followed up on, an inordinate focus on half-baked live-action sequences (not helped by actors who would rather be anywhere else right now), and an uncomfortable amount of adult jokes that felt uncomfortably fetishistic at times. Kung Fu Panda 4, on the other hand, is hurt by an emphasis on comedy at the expense of the emotional storytelling that made the previous films so beloved, an underwhelming villain, and enough continuity errors to make you wonder if the writers even saw the last three films. The banter between Ping and Li Shan was pretty entertaining (seriously, it’s almost scary how much energy James Hong still has even in his mid-90s). Other than that, though, it’s enough to make you wonder why Dreamworks bothered to resurrect the franchise in the first place.

This other ground rule holds for every animated film list going forward, and it may be controversial, but I feel it’s important: no Disney movies. I’m sorry, but given how many different controversies have plagued the happiest place on Earth in the last few years, and given their virtual monopoly power over the entertainment industry, I don’t feel comfortable giving them any free promotion. I don’t care how good Inside Out 2 or Zootopia 2 supposedly are, because, frankly, those are only the exceptions that prove the rule. Disney has made a lot more misses than hits lately, making it clear that quality control has taken a back seat to growing its already obscenely high profit margins (which, admittedly, is probably not helped by me still being subscribed to Disney+, despite my list of reasons not to be seemingly growing longer and longer by the day). I get it: You have nostalgia for Disney. I have nostalgia for Disney. We all have nostalgia for Disney. But the fact of the matter is that the Walt Disney Company that gave us Fantasia, The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, The Little Mermaid, and all the other classics died a long time ago, and the Walt Disney Company of the 21st century doesn’t deserve even a tenth of the reverence of its 20th-century counterpart.

So let’s look at some films from this year that do deserve our reverence, shall we? But before we get to my picks for the ten best animated films of 2024, let’s look at some honorable mentions:

From Ground Zero: I admit that I’m stretching the definition of “animated movie” with this one, since only two out of the 22 short films are actually animated (and that’s only if you count the marionettes in the final segment, “Awakening,” as a form of animation, which I usually don’t, but for the sake of including it in this article, it counts). Still, given that it’s premised on gathering 22 Palestinian filmmakers together to share their unique perspectives on the ongoing genocide in Gaza, there was no way I could go without at least giving it a mention. Much like No Other Land, it is an essential film in helping others to understand that criticism of Israel is not always rooted in antisemitism.

The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim: I wish I could say this anime reinterpretation of Middle-Earth is better than its status as a contractual obligation for New Line Cinema to keep the film rights to The Lord of the Rings, but it definitely isn’t. It may not live up to its potential, but it has enough well-done action sequences and a larger-than-life performance from Brian Cox as Helm Hammerhand to help make it an entertaining watch nonetheless.

That Christmas: Speaking of Brian Cox, his go at voicing Santa Claus is just one of the great things about this film that can be considered a kid-friendly version of Love, Actually (which is unsurprising when you consider that it is based on a series of books written by the same guy who wrote and directed that movie). It’s got wonderful characters, beautiful animation, and multiple plot threads that help the world feel rich and complex without alienating its child audience. It even manages to sneak in a few twists and turns (like Santa’s test to see if the “naughty” twin, Sam, really is as naughty as everyone thinks she is). Only time will tell if it becomes a beloved Christmas classic, but I can easily see myself making this a new holiday tradition alongside The Muppet Christmas Carol and Klaus.

Ghost Cat Anzu: This wonderfully strange Japanese/French co-production uses beautifully executed rotoscoped animation to tell a weird yet heartfelt story about an 11-year-old girl named Karin, neglected by her gambling-addict father, who befriends the titular bakeneko and embarks on a journey through the underworld to reunite with her dead mother’s spirit. Some may take issue with the pacing (the trip to Hell story doesn’t start until an hour in, and we spend most of that hour wandering around the village where Karin and Anzu live), but it’s worth it to experience the film’s crazy yokai designs and its whacky Spirited Away meets Looney Tunes energy.

Speaking of Looney Tunes…

Number Ten

Distributor: Ketchup Entertainment

Production company: Warner Bros. Entertainment

Director: Peter Browngardt

Writers: Darrick Bachman, Peter Browngardt, Kevin Costello, Andrew Dickman, David Gemmill, Alex Kirwan, Ryan Kramer, Jason Reicher, Michael Ruocco, Johnny Ryan, Eddie Trigueros

Music: Joshua Moshier

While not as egregiously screwed over as Coyote vs. Acme (at least this one didn’t need a massive online backlash to get released), The Day the Earth Blew Up still had to fight a bit to get a proper release, as David Zaslav had its HBO Max release canceled in favor of selling it off to Ketchup Entertainment for a limited theatrical release. Fortunately, though, the film proved successful enough that Coyote vs. Acme was released from tax write-off purgatory, and it showed how beloved the Looney Tunes still are even after all these years.

Playing out as a parody of 1950’s science-fiction B-movies, the plot centers on Daffy Duck and Porky Pig (both voiced by Eric Bauza) as their financial struggles leave them in danger of losing the house bequeathed to them by their deceased adoptive father, Farmer Jim (Fred Tatasciore), which isn’t helped when a passing meteorite leaves a giant hole in their roof. They manage to get a job at the local chewing gum factory, where Porky develops feelings for flavor scientist Petunia Pig (Candi Milo). But the trio soon find themselves on an adventure that’s literally out of this world when an alien invader (Peter MacNicol) contaminates the gum with a mutagen that turns everyone in town, except them, into mindless zombies. But can Daffy and Porky overcome their differences long enough to work together and stop the threat that could end life on Earth as we know it?

There’s not that much to say about The Day the Earth Blew Up. It’s just a funny and frenetic romp, like all of the best Looney Tunes creations. It’s definitely great to see a fully 2D animated feature show up in theaters again after so long, let alone one with animation this good (fun fact: this is the first theatrical Looney Tunes film to be fully animated and original (that is, not featuring any preexisting shorts). The regular Looney Tunes stuff is great on its own, but it also manages to sneak in some more experimental sequences, like the Art Deco-inspired “Push the Button, Pull the Crank” scene, and the way Farmer Jim is animated like a stiff cardboard cutout until he abruptly shifts into being animated on ones as he ascends to Heaven.

The music is excellent as well, perfectly matching Carl W. Stalling’s compositions for the original shorts (the interpolation of the classic jazz tune “Powerhouse” into “Push the Button, Pull the Crank” is a special highlight). The movie even makes good use of a few licensed tracks, including R.E.M.’s “It’s the End of the World as We Know It” during the epic battle with the bubblegum zombies and a semi-ironic use of Bryan Adams’ “(Everything I Do) I Do It for You.”

The script successfully balances the zany comedy you’d expect from a Looney Tunes story with a surprisingly poignant emotional core by examining how Porky and Daffy contrast with one another. Porky is a straight-laced everyman who often becomes frustrated with Daffy’s incompetence and eccentricities, at first thinking that his warnings about the gum turning people into zombies are just another insane conspiracy theory he believes. Even when Daffy is proven correct, Porky still refuses to trust him enough not to screw up the effort to stop the alien invasion. In the end, though, Porky is forced to realize that Daffy’s kookiness is probably exactly what is required to save the Earth from certain destruction.

The most I can criticize this film for is the ending fakeout, which I don’t think anyone above the age of seven will buy for a second. Even so, this is the perfect film to introduce 21st-century youth to some of the most beloved cartoon characters ever created. It’s funny, it’s action-packed, and it’s got heart. David Zaslav may not care about Looney Tunes, but The Day the Earth Blew Up is proof that they’re going to be around for a long time.

Number Nine

Distributor: Netflix

Production companies: Netflix Animation Studios, Tsuburaya Productions, Industrial Light & Magic

Director: Shannon Tindle

Writers: Shannon Tindle, Marc Haimes (based on characters created by Eiji Tsuburaya, Tetsuo Kinjo, Tohl Narita, and Kazuho Mitsuta)

Producers: Tom Knott, Lisa M. Poole

Music: Scot Stafford

Netflix’s take on the popular Japanese tokusatsu/kaiju franchise follows professional baseball player Kenji Sato (Christopher Sean), who has been growing increasingly frustrated trying to balance his sports career with his calling as the superhero Ultraman, who transforms into a fifty-foot giant to protect Japan from rampaging monsters. His situation isn’t helped when, as he fights the dragonlike kaiju Gigantron, he finds the monster’s egg, which he has to hide from his rivals at the Kaiju Defence Force. The egg hatches, and the bus-sized baby, which Ken names Emi, imprints on him. As Ken struggles to balance his two careers with caring for his adoptive offspring, he comes into conflict with his estranged father, former Ultraman Hayao Sato (Gedde Watanabe), who he’s forced to rely on alongside his AI assistant, Mina (Tamlyn Tomita), to take care of Emi, and KDF head Dr. Onda (Keone Young), who has his own nefarious plan for Emi…

Rising is an interesting subversion of the typical kaiju story in that it focuses less on monster-fighting action and more on, of all things, being a parent to a young kaiju. It turns out that that’s exactly what Ken needs, as it helps him grow from being a selfish, showboating attention whore (whose performance as Ultraman is often criticized for not caring to avoid too much collateral damage) into a more selfless and caring individual as he grows more and more fond of his monstrous adoptive daughter. His character development is especially believable thanks to the film’s unsentimental look at how difficult parenting can actually be, especially when your child is twenty feet tall.

The painted CG animation helps give this film a distinct look, especially during the action scenes. Also helping with this is Shannon Tindle’s character designs, which put a strong emphasis on sharp angles and thick outlines (if you’re wondering why the aesthetic might seem familiar, Tindle was the character designer and co-writer of Laika’s Kubo and the Two Strings, and was going to direct until Travis Knight forced him off the project).

The film does stumble a bit in portraying the motives of some of its characters. While Ken’s relationship with his father (which was strained by the latter’s duties as Ultraman and perceived lack of interest in his wife’s disappearance) does somewhat work as a nice parallel to Ken’s relationship with Emi, some critics have argued that the film doesn’t do enough to address his more domineering traits, like forcing Ken to take up the mantle of Ultraman despite his son’s true passion being baseball. Meanwhile, some others find themselves more sympathetic to Dr. Onda than to the kaiju, despite his eliminationist goals for them, because of how destructive the animals are (as someone who firmly believes in restructuring human society to make it as undistruptive to the natural world as possible, I respectfully disagree). Still, not all of the character relationships are undercooked. I appreciated how the writers didn’t go the easy route of making Ami Wakita (Julia Harriman) a love interest for Ken, instead merely a confidant to help ease Ken’s anxieties about being a new parent.

I’ve never seen any other entries in the Ultraman franchise, and I’m definitely not much of a tokusatsu fan, so that’s probably not going to change anytime soon. But you don’t need intimate knowledge of the franchise at large to enjoy Ultraman: Rising. It’s got a fun and unexpected twist on the giant monster genre with a surprising emphasis on father-son relationships. I certainly wasn’t expecting anything like that when I first watched it, but I’m definitely happy with what I got.

Number Eight

Distributors: Focus Features, Universal Pictures

Production companies: The Lego Group, Tremolo Productions, I Am Other

Director: Morgan Neville

Writers: Morgan Neville, Aaron Wickenden, Oscar Vazquez, Jason Zeldes

Producers: Pharrell Williams, Mimi Valdes, Caitrin Rodgers, Morgan Neville, Shani Saxon

Music: Michael Andrews (score); Pharrell Williams (songs)

I’ve covered two other animated documentaries on this blog before, both of which were depressing looks at how war and authoritarian governments ruin everything for everyone who gets caught up in them. Piece by Piece definitely isn’t, though, as it’s more of a straight biopic of the legendary hip-hop/R&B singer-songwriter and producer Pharrell Williams, but with the twist of it being told entirely through Legos (or rather, computer animation made to look like Lego sets).

Such a strange artistic decision makes a surprising amount of sense as the film progresses, especially in how it visualizes Pharrell’s synesthesia and portrays the various beats he comes up with as stacks of abstract bricks that pulse and bounce to the rhythm. It also fits with the singer’s famously irreverent personality, and acts as a fun twist on the often trite and cliched musical biopic formula. Some might even compare it to the Robbie Williams vehicle Better Man, which famously portrayed its star as a motion-captured chimpanzee.

Piece by Piece also illustrates Pharrell’s massive influence on the recording industry via interviews with the numerous musicians he’s worked with, from his mentor Teddy Riley and people he grew up with in Virginia Beach (Missy Elliot, Pusha T, Timbaland, and his bandmates in N.E.R.D., Chad Hugo and Shay Haley) to hip-hop and R&B legends like Jay-Z, Kendrick Lamar, Busta Rhymes, and Justin Timberlake and more unexpected collabs like No Doubt and Daft Punk. The interview with Snoop Dogg is a special highlight for how it sneaks in his famous stoner habits via “PG spray.” That’s just one of several clever visual gags, as is Lego Pharrell’s vain attempts to replicate Spock’s Vulcan salute with his claw hands and his parents’ reaction to his appearance in the music video for Wreckx-n-Effect’s “Rump Shaker.”

The presentation isn’t perfect, however. The part discussing Pharrell’s low point felt more like an attempt to fit his real-life story into a Hollywood formula that doesn’t feel natural, and it might gloss over too many details about his creative process for more musically inclined viewers. Still, Piece by Piece manages to avoid the worst traits of the Hollywood music biopic not only through its unique presentation but also by focusing on a celebrity who doesn’t feel full of himself. All that, plus its well-executed messages of self-acceptance and building things up better than you found them, makes for a joyous celebration of creativity centering on one of the most influential American musicians of the 21st century.

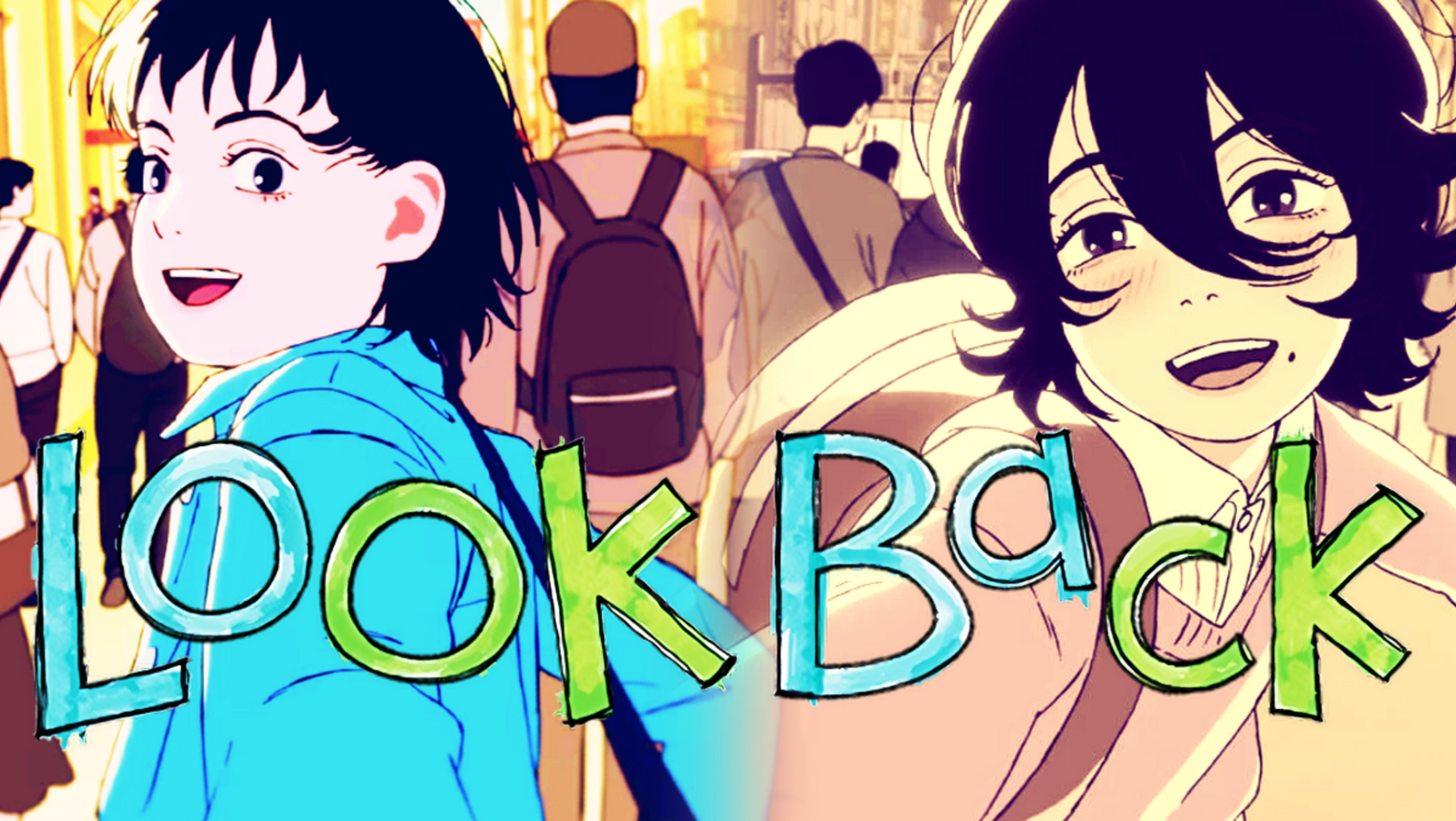

Number Seven

Distributor: Avex Pictures

Production company: Studio Durian

Director/writer: Kiyotaka Oshiyama (based on the manga by Tatsuki Fujimoto)

Music: Haruka Nakamura

You probably wouldn’t expect such a bittersweet and down-to-earth tale about the triumphs and tragedies of creating art to come from the same guy who created Chainsaw Man. Yet this semi-autobiographical tale achieves a universality that transcends its examinations of manga creation and speaks to artists everywhere with its questions as to why we create art in the first place.

The avatars Fujimoto uses to convey these questions are an extroverted aspiring manga writer named Ayumu Fujino (Yuumi Kawai/Valerie Rose Lohman) and a talented background illustrator named Kyomoto (Mizuki Yoshida/Grace Lu), who suffers from social anxiety so severe that she’s had to withdraw from school. They start out as rivals when the quality of Kyomoto’s work causes Fujino lose confidence in her abilities and stop drawing for a year. When Fujino visits Kyomoto’s house to hand deliver her diploma, however, the latter unexpectedly bursts out and proclaims herself Fujino’s biggest fan, not only rekindling Fujino’s creative spark but also inspiring a fulfilling artistic collaboration that lasts throughout high school. But as adult life forces them apart in increasingly cruel and tragic ways, Fujino is forced to confront her imposter syndrome and regret to figure out why she still wants to create art in the first place.

One could argue that Look Back is this generation’s answer to Studio Ghibli’s Whisper of the Heart, being another tale about how artistic creation can be both isolating and fulfilling at the same time. The scope of this tale feels a little bigger than Miyazaki’s take, though, especially in the way that Fujimoto chooses to insert a major disaster into the narrative (inspired by both the Kyoto Animation arson attack and his feelings of uselessness as an artist after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami) to ask questions about what art can actually do to help when real life gets especially horrible and unbearable.

Indeed, Fujino and Kyomoto’s struggles hit very close to home for me, as I struggle with similar issues as an aspiring writer myself. I struggle with self-esteem and motivation like Fujino, and I struggle with reclusive and asocial habits like Kyomoto, and unlike her, I haven’t yet found anyone who can honestly make me say, “I’m glad I came out of my room.” I still feel an urge to let the stories inside of me out, but I also struggle with the gnawing fear that I don’t have the talent necessary to do them justice, that I’d be making a mockery of them by trying to tell them myself.

It’s certainly a testament to this creative team’s storytelling abilities that they manage to pack a story with such emotional heft into a film that’s not even an hour long. I didn’t even get into the possibly real, possibly imagined climactic time travel sequence where Fujino works through her guilt over how her and Kyomoto’s friendship ended, where all of the film’s philosophical ponderances come to a head in a satisfying yet ambiguous way. It didn’t solve any similar problems I had, but that’s probably something better worked out between my therapist and me.

Perhaps Indiewire’s review puts it best: “Making things isn’t a waste of time or a way of isolating oneself from the world, but rather the most beautiful way of belonging to it.” Indeed, Fujimoto managed to pull himself out of his post-earthquake funk and turn it into the original Look Back manga. Stories like this give truth to Robin Williams’ assertion in Dead Poets Society that “Poetry, beauty, romance, and love are what we stay alive for.” Art is often what gets us through hard times by showing us fellow humans pouring out their feelings on the canvas or the page. Perhaps that’s what’s helping me to not give up on my own artistic pursuits: the hope that I make something even half as emotionally affecting as Look Back one day.

Number Six

Distributor: Netflix

Production company: DreamWorks Animation

Director: Sean Charmatz

Writer: Charlie Kaufman (based on the book by Emma Yarlett)

Producer: Peter McCown

Music: Robert Lydecker, Kevin Lax

You can probably imagine my surprise when I logged onto Twitter back in November 2023 and discovered that Charlie Kaufman of all people had signed on to write for an animated DreamWorks film. While Orion and the Dark might not be as mindbendingly surreal as Being John Malkovich, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, or Synechdoche, New York, it still offers its younger audience the same existentialism and layered storytelling that Kaufman’s adult fans are well accustomed to.

The story centers on 11-year-old Orion Mendelson (Jacob Tremblay), who is plagued by an absurdly long list of phobias, some relatively rational (bullies, bees, dogs, talking to his crush, etc.) and others…less so (murderous gutter clowns, carcinogenic cellphone waves, his parents moving away while he’s at school, etc.). But the biggest phobia of all is his fear of the dark, which makes it especially terrifying for him when, one night, the darkness literally comes alive and decides to take Orion on an adventure to face his fears. Dark (Paul Walter Hauser) introduces Orion to the other entities of the night: Sleep (Natasia Demetriou), Quiet (Aparna Nancherla), Insomnia (Nat Faxon), Unexplained Noises (Golda Rosheuvel), and Sweet Dreams (Angela Bassett). Along the way, Orion and the Dark learn valuable lessons about self-esteem and about seeing the beauty in darkness.

The film is probably best summarized by A.A. Dowd of IGN as being Charlie Kaufman’s attempt at doing a Pixar movie. In this case, the typical Pixar formula of “what if (x object/animal/concept) had feelings” is applied to abstract concepts associated with darkness and the night. Dark’s psychological baggage gets especially heavy focus, as he fully admits that he’s developed an inferiority complex thanks to everyone, especially small children, hating and fearing him. The other entities of the night accuse him of selfishly using Orion to boost his own self-esteem and finally convince the world at large that he’s not the terrible figure the world thinks he is (and also to get back at his rival, Light (Ike Bairnholtz)), which doesn’t help matters. Orion himself also feels perfectly at home within Kaufman’s oeuvre of neurotic protagonists (“Fun is just a word people made up to make danger sound more appealing!” he protests at one point). He even explains at one point that his fear of darkness stems from his fear of the nothingness after death (“I try to imagine what death is like. I’ve concluded it’s like nothing. This is black and silent, not nothing. Blackness and silence is something. Nothing is perhaps the one unimaginable thing.”), which is quite a dark element to introduce into a children’s film. You certainly can’t accuse Kaufman of trying to talk down to the audience.

The screenplay is aided by wonderfully appealing animation (which looks all the more impressive when you realize DreamWorks’ TV division did it), excellent voice acting (Hauser is especially effective as Dark with his gruff yet friendly voice), and well-timed comedy. In addition to Orion’s comical overreactions, we have Sleep’s use of metaphysical pillows and chloroform to get people to sleep, the very short documentary about darkness narrated by Werner Herzog, and Orion apparently being a fan of David Foster Wallace.

Some critics have complained about some twists that occur halfway through the narrative, and it’s not hard to imagine some kids getting confused at the metafictional nature of the third act. Still, it wouldn’t be a Charlie Kaufman film if it didn’t have those elements. Even if it’s not flawless, Orion and the Dark is still an ambitious and creative journey into childhood fear and wonder that teaches us to appreciate the more cozy side of darkness.

Number Five

Distributors: BBC, Netflix

Production company: Aardman Animations

Directors: Nick Park, Merlin Crossingham

Writers: Nick Park (story); Mark Burton (story and screenplay)

Producer: Richard Beek

Music: Lorne Balfe, Julian Nott

For about a decade after Wallace’s longtime voice actor, Peter Sallis, retired in 2010 (and subsequently passed away at 96 in 2017), it seemed to be curtains for England’s favorite claymation duo, with Shaun the Sheep having to fill the void as Aardman’s new mascot. However, the company decided that the duo deserved to persevere, not just as another half-hour short but as a full-on feature-length film, and the world couldn’t be happier for it.

In this newest adventure, Wallace (voiced this time by Sallis’ understudy, Ben Whitehead) has made a new invention, Norbot (Reece Shearsmith), who can do anything his master requires, much to Gromit’s chagrin. But the canine companion’s resentment toward his master’s favoritism over the bot soon turns out to be the least of his problems, as Feathers McGraw (the silent penguin antagonist from The Wrong Trousers) remotely hacks Norbot and uses him to steal the blue diamond, framing Wallace for the crime in the process and getting his inventions confiscated by the police. It falls to Gromit to expose his old nemesis’ machinations and clear his master’s name before he’s forever barred from inventing anything ever again.

This installment stays true to W&G’s old-fashioned, nostalgic charm while successfully keeping up with the times, especially in how it handles its themes of overreliance on technology. Wallace’s reliance on his inventions to accomplish simple household tasks is given a critical look by showing how well he would function if he were to suddenly lose all his cracking contraptions, and the answer is…not very well (he doesn’t even remember how to operate a teapot!). The Norbots also serve as Aardman’s way of satirizing AI without drifting into “old man yells at cloud” territory, as they only turn bad thanks to Feathers McGraw’s outside influence and later play a major part in saving the day at the end. This character study gives the film an emotional core that almost no other Wallace and Gromit production has, helping the former realize that technology should be used in moderation, lest you forget how to act like a human.

As can be expected from an Aardman production, the animation and comedy are top-notch. The claymation looks especially well-polished here, which is unsurprising for a team that’s had forty years to perfect its techniques. The comedy includes several subtle in-jokes referencing previous W&G adventures and background gags (“No swearing near the parrot,” advises one sign at the zoo), Gromit falling into a lion enclosure and shoving a “Do not feed!” sign into its mouth, Wallace completely failing at functioning as a human without his contraptions, and the downright brilliant twist of where the blue diamond has been all this time.

It’s not totally flawless. The subplot involving the bumbling police officers Mukherjee (Lauren Patel) and Constable Mackintosh (Peter Kay) never really connects with the main plot in any meaningful way, and the music, aside from Julian Nott’s original themes, isn’t all that memorable. Still, with character arcs this good and its comedy still firing on all cylinders, Vengeance Most Fowl is as much of a cracking good time as any other Wallace and Gromit outing, and proves that they’ll be with us for a long time to come.

Number Four

Distributor: Paramount Pictures

Production companies: Paramount Animation, Hasbro Entertainment, New Republic Pictures, di Bonaventura Pictures, Bayhem Films

Director: Josh Cooley

Writers: Eric Pearson (screenplay); Andrew Barrer, Gabriel Ferarri (story and screenplay)

Producers: Lorenzo di Bonaventura, Tom DeSanto, Don Murphy, Michael Bay, Mark Vahradian, Aaron Dem

Music: Brian Tyler

I’ll admit that I’m mostly an outsider when it comes to the Transformers franchise, so my opinion probably doesn’t count for that much. Still, from my layman’s perspective, Transformers One is a helluva introduction, telling a poignant story of lost friendship amidst the origin story of what’s probably the most famous space opera this side of Star Wars.

The story is set on Cybertron in the distant past, in the wake of a war with the Quintessons, which left the surface uninhabitable, lost them the Matrix of Leadership, and cut off the supply of Energon, forcing lower-class robots to mine it by hand. Among these proletariat androids are Optimus Prime and Megatron, then known as Orion Pax and D-16 (Chris Hemsworth and Brian Tyree Henry, respectively), who learn of a distress signal coming from the surface and decide to go looking for it. Accompanying them are smelting plant worker B-127/Bumblebee (Keegan-Michael Key) and their by-the-book boss, Elita-1 (Scarlett Johansson), who gets stuck on the surface with them while trying to apprehend them. As the quartet explores the surface, they gain the power to transform and also learn some troubling secrets about the Quintesson war that reflect poorly on their leader, Sentinel Prime (John Hamm). These revelations bring out a hidden dark side in D-16 that may not only tear apart his and Orion’s friendship, but also endanger the effort to save their world…

Many fans and critics have hailed it as the best Transformers film since 1986’s The Transformers: The Movie, and for good reason. It’s got excellent animation, which complements the kinetic action sequences very well (it also lends itself well to Cybertron’s beautifully chaotic surface vistas). The celebrity voice actors (also including Laurence Fishburne as the ancient Prime Alpha Trion and Steve Buscemi as Starscream) are well cast and deliver committed, flawless performances. Well…mostly; Chris Hemsworth’s attempts at mimicking Peter Cullen in a few spots feel a little too forced to take seriously, and B-127 dubbing himself as “Badassatron” feels like the writers trying a little too hard to avoid a G-rating. Other than that, though, the screenplay offers a rich and textured portrait of its characters and setting, lending the drama between Orion and D-16 the emotional weight it deserves and offsetting it with some (mostly) well-done comic relief (I especially liked how it takes our heroes a little while to get the hang of their newfound transforming abilities). It also poses pertinent questions asking how far is too far in dealing with oppressive authority figures.

Some have argued that the film is too fast-paced, making D-16’s turn to the dark side feel rushed. I didn’t get that impression when I watched the movie, though, and even if it was rushed, it still didn’t make his growling “I’m done saving you!” to his former friend feel like any less of a gut punch.

As I said, I’m a Transformers outsider, so maybe my opinions should be taken with a grain of salt. Still, I think Transformers One is an excellent introduction to the franchise, especially for how it presents the origin of one of the most famous fictional rivalries of all time.

Number Three

Distributor: Madman Entertainment

Production companies: Screen Australia, VicScreen, Melbourne International Film Festival Premiere Fund, Arenamedia, Soundfirm, Anton, Charades, Snails Pace Films

Director/writer: Adam Elliot

Producers: Liz Kearney, Adam Elliot

Music: Elena Kats-Chernin

Coming to us from the same director who gave us Mary and Max, this tale of human misfits from Down Under follows Grace Pudel (Sarah Snook/Charlotte Belsey) as she recounts her life story to her pet snail, Sylvia. She tells of how fondly she remembers her father, a French former street performer named Percy (Dominique Pinon), despite him being a paraplegic who turned to the bottle for comfort after his wife died in childbirth. She recalls how other kids used to bully her and her twin brother, Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee/Mason Litsos), for their cleft palate and pyromania, respectively. After Percy’s death, the two were separated and sent to families on opposite sides of Australia. Grace went to Ian and Narelle (Paul Capsis) in Canberra, who often neglected her so they could indulge in their hobbies of netball and nudism, while Gilbert went to a Christian fundamentalist compound near Perth, where the mother, Ruth Appelby (Magda Szubanski), abuses him in an effort to cure him of his pyromania and attraction to her son, Ben (Davey Thompson). Grace, meanwhile, has trouble connecting with others as she grows into adulthood, including getting engaged to a microwave repairman named Ken (Tony Armstrong), who turns out to be keeping a dark secret from her. However, she does make an unlikely friend in the elderly, eccentric former table dancer Pinky (Jacki Weaver), who may be the key to helping Grace move past her trauma and build a new, fulfilling life for herself.

As you may be able to tell from the plot summary, Memoir of a Snail is probably the biggest emotional rollercoaster ride on the list, rivaled only by Look Back. Despite how cartoonish they look, Adam Elliot’s characters feel more real than many live-action protagonists, thanks to the quirks and idiosyncrasies he gives them. The muted color palette and grimy aesthetic, combined with their cartoonish look, complement the bittersweet tone, giving us a world full of misfits and outcasts. We see the toll that society’s rejection has taken on them, yet also see them finding community and support with one another despite it.

The voice cast helps immensely in getting us to empathize with these misfits, especially Snook (voicing Grace with soft-spoken sincerity) and Weaver (who is a riot as the gravelly-voiced free-spirited Pinky). Other notable names in the voice cast include Eric Bana (who voices a judge who became homeless after he was caught masturbating in court and later repays a kind act from Grace in a big way) and Nick Cave (who voices a love poem from Pinky’s second husband in the most cheesily over-the-top way). The film also offers plenty of comedy to balance out the darkness, from Pinky’s husbands constantly dying in bizarre freak accidents to young Grace’s squicked-out reaction to watching snails have sex to Pinky losing her job as a school crossing guard when she accidentally teaches a naughty word to the kids when a careless driver almost runs her over.

I haven’t seen Elliot’s other masterwork, Mary and Max, yet, which seems weird since I’m autistic and that film is known for some of the best neurodivergent representation in the medium. However, if that film’s exploration of the way society’s outcasts live is even half as good as what we got in Memoir of a Snail, then maybe I should set aside a slot in the next episode of “1001 Animations” to talk about it.

Flow

Distributors: Baltic Content Media, UFO Distribution, Le Parc Distribution

Production companies: Sacrebleu Productions, Take Five, Dream Well Studio

Director: Gints Zilbalodis

Writers: Gints Zilbalodis, Matiss Kaza

Producers: Matiss Kaza, Gints Zilbalodis, Ron Dyens, Gregory Zalcman

Music: Gints Zilbalodis, Rihards Zalupe

Okay, stop me if you’ve heard this one: A black cat, a yellow lab, a capybara, a ring-tailed lemur, and a secretary bird walk onto a sailboat…

But what these animals go through in the film is no joke. In a fantasy world where humanity seems to have inexplicably vanished, a solitary cat is simply trying to eke out an existence in its former master’s house (and trying to elude a pack of feral dogs) when it is suddenly caught up in a flash flood. It manages to find safety when a sailboat drifts past, but is surprised to see a capybara already occupying it. As the animals pilot the boat toward a massive set of stone pillars rising in the distance, they are joined by a yellow lab from the dog pack (which is much friendlier than the others), a ring-tailed lemur with a bad habit of hoarding shiny objects, and a secretary bird that gets its wing injured when it stops other memebers of its flock from eating the cat. It’s certainly an odd grouping, and not one naturally inclined to get along easily. Still, as the adventure continues and the boat draws closer to the pillars, the animals will need to set aside their differences and work together to survive this disaster.

It’s safe to say that nothing in the last few decades of animated film has felt quite as unique as Flow. It’s undoubtedly the most innovative: it was mostly animated using the open-source software Blender, which gives it an absolutely gorgeous painted CG art style, making it among the most beautiful apocalypses ever put on the silver screen. This is aided by several long takes, such as the cat’s underwater adventure to escape the marauding secretary birds and the lemur’s invitation aboard the sailboat, apparently influenced by the filmmaking techniques of Jacques Tati and Alfonso Cuarón.

The decision to make the animals normal and non-talking also supports the film’s sense of mystery and mystique, leaving us viewers just as in the dark about what is going on as our animal protagonists. The director has since claimed that the story was a semi-autobiographical examination of how he was forced to overcome his natural introversion to get the film made, but this film could just as easily be seen as an anti-racist/anti-nationalist allegory, a metaphor for climate change, or a Biblical narrative (especially with the portal that shows up in the climax and the whale-like sea monster that occaisionally shows up to help the protagonists out of a sticky situation).

That’s the neat thing about ambiguous films like Flow: they can be about practically anything you want them to be. My big takeaway from it was the idea of going outside your comfort zone, probably best demonstrated by the cat overcoming its fear of water to dive under and grab some fish to help the sailboat crew sustain themselves for the long journey.

All of this helped carry Flow to a well-deserved Oscar for Best Animated Feature at the 97th Academy Awards, the first independent feature to win the award. It really is a one-of-a-kind film: an independent feature that rivals Disney and DreamWorks in popularity, that can be enjoyed equally well by kids and their parents, and feels like it’s actually helping the field of animation to evolve. It’s a perfect demonstration that, as IndieWire reviewer Christian Blauvelt put it, “lost things can be found again.”

The Wild Robot

Distributor: Universal Pictures

Production company: DreamWorks Animation

Director/writer: Chris Sanders (based on the novel by Peter Brown)

Producer: Jeff Hermann

Music: Kris Bowers

This naturalistic sci-fi epic marks the end of an era for DreamWorks Animation, as it was the last film produced by its in-house animation team before they decided to outsource animation work as a cost-cutting measure. If you ask me, though, they couldn’t have picked a more beautiful film to go out on.

The story follows ROZZUM 7134 (Lupita Nyong’o), aka Roz, who finds herself marooned on an uninhabited island after a storm washes her off a cargo ship. Well, “uninhabited” may be the wrong word, as the island has a teeming ecosystem full of animal life, none of which wants anything to do with the weird metal monster that has just shown up on their doorstep. One especially violent encounter with the local grizzly bear, Thorn (Mark Hammill), causes Roz to accidentally crush a goose nest, killing the mother and all but one of the eggs. When the egg hatches into a young male gosling, whom she names Brightbill (Boone Storme/Kit Connor), she finds a new purpose in raising the defenseless chick to adulthood. She receives help in the form of a cunning yet sympathetic fox named Fink (Pedro Pascal) and an empathetic opossum named Pinktail (Catherine O’Hara in her last film role (rest in peace, queen)), who acts as a confidant for Brightbill’s mechanical mom. But will Roz carve out a new spot for herself as a friend to the animals on her island, or will she one day have to return to the human world she was built to serve, especially after Brightbill learns the truth about what happened to his biological mother?

Admittedly, The Wild Robot isn’t breaking new ground with its story about a robot that grows beyond its programming and learns human emotions (a la Wall-E and The Iron Giant) and a child struggling to accept their adoptive parent. Indeed, Chris Sanders has built a whole career around the “outcast kid bonds with outcast animal” premise, with previous films like Lilo and Stitch and How to Train Your Dragon. However, many viewers and critics agree that the film’s beautiful execution of these tropes helps them rise beyond their derivative nature.

Part of what helps is the way the script stays true to DreamWorks’ trademark edginess by showing the darker aspects of the natural world via well-placed black comedy, like Roz asking a crab if it needs assistance, only to see it snatched away by a gull; Fink reminiscing about his mother rocking him to sleep by bashing his head in with a rock; and practically everything that happens during Roz’s first meeting with Pinktail (“As a mother of seven…” chomp “AHHHH!!!” “…of six kids…”). All of this silliness is balanced by plenty of heart-tugging sincerity, especially in showing Roz and Brightbill’s evolving relationship and Fink’s overcoming his rough childhood to become a worthy father figure to Brightbill.

The excellent voice cast helps in this regard. The main trio of Nyong’o, Pascal, and Connor give knockout performances, with Nyong’o perfectly capturing Roz’s gradual evolution from a cold mechanical machine to a being with complex human emotions, Pascal excellently capturing Fink’s sly and foxy nature while also showing a more vulnerable and loyal side (Pascal even called Fink one of the more relatable characters he’s played), and Connor pulling a stunning range of emotion even as he’s faking an American accent. O’Hara and Hammill also shine as the jaded yet empathetic Pinktail and the cantankerous Thorn, who warms up to Roz after she saves his and all the other animals’ lives during a blizzard. Other notable actors I haven’t mentioned include Ving Rhames as Thunderbolt (a dramatic peregrine falcon who teaches Brightbill how to fly), Matt Berry as Paddler (an arrogant beaver hellbent on felling the largest tree on the island), Bill Nighy as Longneck (an elder goose who takes Brightbill under his wing), and Stephanie Hsu as Vontra (a psychotic robot sent by Universal Dynamics to retrieve Roz).

“But wait,” I hear some of you ask, “is The Wild Robot really better than Flow?” I don’t really know, to be honest. It’s kind of a toss-up. Flow is by far the bigger artistic accomplishment of the two, and it definitely deserved the Oscar over the former. Still, I could see some becoming alienated by the way the story throws you into a strange, ambiguous situation with little to no explanation. Others might counter by pointing out the rather clichéd plot structure of The Wild Robot, although, as I’ve hopefully pointed out, it’s not the clichés themselves that make the film, but rather how they are executed. The Wild Robot executes them beautifully with committed voice actors, a script that knows how to balance black comedy with well-earned emotions, and painted CG animation every bit as good as what Flow has to offer (standout sequences include the butterfly swarm and the way Roz glows when Brightbill imprints on her and she discovers her purpose).

The Wild Robot, along with Flow, is another glorious exhibit in the argument against those who say animation is only for kids and can never be true cinema, one that I think many parents will find poignantly relatable.

And so my list of my favorite animated films of 2024 is finally complete…at the start of February 2024. Like I said at the beginning, I was going through some stuff in 2024. Still, I promised I would get it out, and here it is!

As I said in the New Year’s update, animation retrospectives will be the focus for the next few months, and the 2024 animated series list should be released either later this month or in early March. Before I start that, though, I will be bringing P.J.’s Ultimate Playlist out of hibernation to give myself a shorter, less labor-intensive article to fill out the gap, where I’ll be discussing a song about societal collapse from one of the weirder bands to come out of the early 1970s prog rock renaissance.

And that’s all I have to say about animated cinema for now. Stay looney, fellow animaniacs!