The 1001 Animations Christmas Special! (#31-40)

It has occurred to me, in looking over the various Christmas-themed articles I’ve written, that much of my Yultide blogging has focused a little too much on some of the worst pieces of holiday-themed “entertainment” that the industry has inflicted upon us, as well as an update post talking about my personal struggles and my then-recently deceased grandmother. I think it’s about time that I let the PrestonPosits audience see some tenderness connected with the most wonderful time of the year for a change, and, luckily, my “1001 Animations You Must See Before You Die” has just what jolly old Saint Nick ordered for such an occasion.

Several holiday classics made it onto my list, and I want to share my thoughts on 10 of them with you this December. They include some adaptations of A Christmas Carol, two very different adaptations of a wintry Hans Christian Anderson story, one of the most famous stop-motion films of all time, an unexpected Japanese adventure starring a trio of homeless outcasts and an abandoned baby, and an old short that’s surprisingly cute for being set in a post-apocalyptic world where humans have gone extinct.

As you can probably see, we have quite a ride ahead of us, so let’s get going on this mini-joyride through the history of the greatest Christmas specials of all time, shall we?

#57: Peace on Earth

Animation style: Traditional 2D

Release date: December 9, 1939

Distributor: Loew’s Inc.

Production companies: Harman-Ising Productions, MGM Cartoons

Director: Hugh Harman

Writers: Jack Cosgriff, Charles McGirl

Producers: Hugh Harman, Fred Quimby

Music: Scott Bradley

Don’t let the cutesy image above fool you: This classic short might be the darkest one on this list, given its thematic content. Sure, it stars cute talking animals, but these animals live in the ruins of a world where humans drove themselves to extinction through constant warfare.

We see this through the eyes of a kindly old squirrel (voiced by the legendary Mel Blanc) who explains the story to his two grandchildren when they ask him who the “men” in the phrase “peace on Earth, goodwill to men” are. Grandpa explains that when he was their age, he and the other animals in their village witnessed the constant wars the human race would cook up and the increasingly ridiculous excuses they would come up with to keep fighting (flat-foots vs. buck-teeth, vegetarians vs. meat-eaters, etc.). The men continued fighting until the last two that were left on either side shot and killed each other simultaneously, thus dooming their species to extinction. The animals then found a Bible in a ruined church (“Looks like a mighty good book of rules,” says the wise old owl, “but I guess them men didn’t pay much attention to them”) and were inspired to rebuild by Isaiah 61:4 (“And they shall build the old wastes, they shall raise up the former desolations, and they shall reapir the waste cities, the desolations of many generations”). Thus, the animals have dedicated themselves to restoring the world and not repeating the mistakes humankind made in the previous era.

Some might get turned off by how preachy and unsubtle the message is, especially given the short’s historical context (it premiered three months after the start of World War II, well before most of the world knew the full depths of depravity Hitler’s Germany would sink to). The scene where the owl explains to the squirrel about how “Thou shalt not kill” is a good rule to live by might also be hard to take seriously, given how owls eat squirrels in real life, as is the prospect of humanity driving itself to extinction using only World War I-era weaponry.

Still, one cannot deny how forcefully the short makes its point about how frivolous war really is in the grand scheme of things, especially given the silly reasons Grandpa Squirrel gives for humans continuing to fight each other until the bitter end, and the way it outright condemns war as sacrilegious with the way it invokes the Bible. The short also goes out of its way to make the war sequences look as hellish as possible, further driving home the point, especially in how the soldiers are animated via rotoscope to look as uncanny as possible. Grandpa Squirrel’s recollections of humans as monstrous creatures (especially in the way he mistakes the filter hoses on their gas masks for “long snouts that went into their stomachs”) also adds a nice touch of xenofictional spice to the narrative.

While the part about humanity driving itself to extinction might have seemed overblown back in 1939 with the comparatively crude war machines of the era, it wouldn’t stay that way after atomic bombs were invented and used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. William Hanna and Joseph Barbera agreed so strongly that they even teamed up with MGM Cartoons in 1955 to create a remake of Peace on Earth, under the new title Good Will to Men. The talking animal sequences are essentially the same as the original, except this time we follow an elderly mouse deacon as he tells his mousey choirboys the story of humanity’s downfall. The short makes up for the recycled script, however, by making the war sequences arguably even more nightmarish than the original, which certainly wasn’t hard to accomplish given all the new military technology that had been invented in the 16-year interim, including bazookas, flamethrowers, and, of course, nuclear warheads. Indeed, it is the latter that drives humanity to extinction in this version. While the nuclear holocaust scene here is more abstract in its presentation and thus not quite as viscerally horrifying as those in works like Barefoot Gen or When the Wind Blows, the two shock waves overlapping each other in a Venn diagram of death and destruction still leave quite an impact.

More conservative types can scoff and dismiss the message of these shorts as hippy-dippy bullshit all they like (as well as its spot on Jerry Beck’s list of the 50 greatest cartoons of all time), but the truth is that war is a stupid and pointless endeavor. I can only hope that one day, the countries of this world (especially my own) will finally take the message of Peace on Earth or Good Will to Men to heart and finally stop cooking up new wars for their young men and women to die in.

#156: The Snow Queen

Animation style: Traditional 2D

Release date: November 1, 1957

Distributor: Universal-International

Production company: Soyuzmultfilm

Director/producer: Lev Atamanov

Writers: Lev Atamanov, Nikolai Erdman, Georgy Grebner (based on the fairy tale by Hans Christian Andersen)

Music: Artemi Ayvazyan (score); Nikolay Zabolotsky (songs)

It’s somewhat tempting to just point out that this film is Hayao Miyazaki’s favorite film and leave it at that. Indeed, Miyazaki has claimed that if he hadn’t seen it in 1963, when he was getting his start as an animator at Toei Animation, he probably would have given up on the industry altogether, meaning that Studio Ghibli likely would never have come into existence. But there’s a lot more to this film’s place in animation history than its relevance to Japan’s greatest living animator.

The story is narrated to us by a diminutive wizard named Ol’ Dreamy (Vladimir Gribkov/ Paul Frees), who tells of how childhood friends Gerda (Yanina Zhejmo/Sandra Dee) and Kai (Anna Komolova/Tommy Kirk) learn about the existence of the Snow Queen (Maria Babanova/Louise Arthur) from Gerda’s grandmother (Vera Popova/Lilian Buyeff). When Kai makes a joke about melting the Snow Queen on a hot stove, she smashes her magic mirror and sends shards into Kai’s eye and heart, causing him to become cruel to Gerda. When the Snow Queen later comes to their village and takes Kai to her icy palace in the Arctic, Gerda makes it her mission to rescue her best friend from the Snow Queen’s clutches and restore kindness to his frozen heart.

The Snow Queen is undoubtedly one of the most famous works of animation to come out of Eastern Europe and was made possible, in part, by Nikita Kruschev’s de-Stalinization policies after his predecessor’s passing, which allowed the filmmakers much more artistic freedom than they would have had when Stalin was in power. Granted, there were still some limits. For instance, they weren’t allowed to travel beyond the Iron Curtain to Denmark to visit Andersen’s homeland, so they had to seek out inspiration in Latvia and Estonia instead. They also had to excise several of the more overtly Christian elements in accordance with the Soviet Union’s hardline anti-religion policies (the Snow Queen’s magic mirror being made by Satan himself, for instance). However, such elements aren’t important enough to the story for their absence to be missed.

The result is a sublime piece of animation. It’s definitely significantly influenced by Walt Disney, but it’s definitely no Disney rip-off. The animation is colorful and vibrant (the Snow Queen herself deserves special mention, as she was rotoscoped over footage of her actress, Maria Babanova, to emphasize her otherworldly nature). The characters are a bit simplistic by modern standards, but it’s hard not to empathize with Gerda, given the often hellish journey she has to go on to rescue Kai, from the fairy lotus eater trap to the raging blizzards to the gang of robbers. Gerda’s relationship with the robber girl (Galina Kozhakina/Patty McCormack) is especially interesting, as the latter starts out as a ruthless thief with a menagerie of wild animals as pets but becomes so moved by Gerda’s kindness that she tearfully sets them all free. Beyond the whole theme of “kindness is never wasted” that the film seems to be going for, it’s not difficult to read some queer subtext into the scene (which, if you know anything about Hans Christian Andersen’s personal life, is probably not surprising).

If there is one thing I can criticize this film for, it’s that the Snow Queen’s characterization feels somewhat inconsistent. She starts the whole conflict by cursing Kai over a harmless joke, which makes her seem petty and thin-skinned. But then, when Gerda cures Kai of the curse and tells the Snow Queen to back off, the icy witch just lets them go without a fight. This also makes the film end rather anticlimactically.

Even so, The Snow Queen is still essential viewing for anyone interested in animation history, especially those interested in Eastern European animation. Perhaps Miyazaki himself said it best:

Snedroningen [the film’s Danish title] is proof of how much love can be invested in the act of making drawings move, and how much the movement of drawings can be subliminated into the process of acting. It proves that when it comes to depicting simple yet strong, powerful, piercing emotions in an earnest and pure fashion, animation can fully hold its own with the best of what other media genres can offer, moving us powerfully.

-Miyazaki, Hayao (2009) [1996]. Starting Point: 1979–1996. Viz Media. ISBN 978-1-4215-6104-2.

#240: A Christmas Carol

Animation style: Traditional 2D

Release date: December 21, 1971

Distributor: ABC

Production company: Richard Williams Productions

Director: Richard Williams

Writer: Charles Dickens (based on his novella A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas)

Producers: Richard Williams, Chuck Jones

Music: Tristram Cary

A Christmas Carol is one of the most widely adapted English-language works ever, so it can often be challenging to do it in a way that gives your version its own identity. That probably wasn’t a problem for the legendary Richard Williams, who composed his version while taking a break from his ill-fated magnum opus, The Thief and the Cobbler. The result has been remembered as one of the most surreal and frightening adaptations of Charles Dickens’s classic, as it reminds us just how morbid a ghost story this timeless tale is.

The story (narrated by Michael Redgrave), as Dickens originally wrote it, is surprisingly intact for such a short runtime (the special runs just 25 minutes). Not only are all the crucial plot beats preserved, but the special even manages to fit in several details from the book that even most feature-length adaptations tend to omit, like Scrooge (Alastair Sim, reprising his role from the 1951 adaptation Scrooge) extinguishing the Ghost of Christmas Past (Diana Quick) with their giant candle snuffer, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come forcing Scrooge to confront his shrouded corpse, and the Ghost of Christmas Present (Felix Felton) showing Scrooge several lonely, isolated people (miners, lighthouse keepers, sailors, etc.) still keeping the Christmas spirit despite their solitude.

Of course, what most viewers probably remember most are the several scenes that lean into the nightmarish ghost-story elements of the original. For instance, this is one of the few adaptations to include Jacob Marley’s (Michael Hordern, also reprising his role from Scrooge) jaw falling onto his chest when he unties his bandage. The Ghost of Christmas Past’s design here may be the closest to the way Dickens described them, as Williams portrays them as shimmering like a candle flame, with their face and body parts often appearing as multiple after-images stacked atop one another, rapidly aging or de-aging in the process. Ignorance and Want look especially ghoulish in their appearance here, and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come looks as creepy and mysterious as ever. Of course, none of this is helped by Williams’ characteristically hyper-detailed animation style (heavily inspired by John Leech’s illustrations in the original edition), which might make even regular human characters like Fred (David Tate) or Fezziwig (Paul Whitsun-Jones) land in the uncanny valley for some viewers. It also doesn’t help that there is very little non-diegetic music outside of the opening and conclusion of the film.

On the other hand, this might be why Williams’ Christmas Carol has been heralded as the best animated adaptation of the novella. It has such high-quality animation for a television special that it was even played in theaters, thus helping it secure the Oscar for Best Animated Short Film at the 45th Academy Awards (although, naturally, several industry insiders with a stick up their ass changed the rules afterward so that a TV special would never again be eligible for the award). All of this is even more remarkable when you consider that, much like other major Richard Williams projects like Raggedy-Ann and Andy and The Thief and the Cobbler, the special suffered from a troubled production cycle, falling several months behind schedule and forcing the animators to pull four all-nighters near the end just to get it out on time, with Williams having to cut corners using rotoscoping in a few scenes just to get it over with. According to animator Tony White, they only finished the special one hour before the deadline.

It’s not perfect by any means, as the short length meant that, for as many vital details of the book that it preserved, just as many were cut. For example, we only spend a few seconds with Bob Crachit (Melvyn Hayes) as he mourns Tiny Tim (Alexander Williams, Richard’s then four-year-old son), and Scrooge’s sister Fan becomes Dame Not-Appearing-in-this-Adaptation. Still, with animation this good and a story this beloved, which the creators clearly did their best to preserve even with the truncated length, it’s no wonder it remains a yuletide cult classic to this day.

#366: Mickey’s Christmas Carol

Animation style: Traditional 2D

Release date: December 16, 1983

Distributor: Buena Vista Distribution

Production company: Walt Disney Productions

Director/producer: Burny Mattinson

Writers: Burny Mattinson, Tony L. Marino, Ed Gombert, Don Griffith, Alan Young, Alan Dinehart (based on the novella by Charles Dickens)

Music: Irwin Kostal

This special was almost certainly my introduction to the most famous Christmas story of all time when I saw it as a kid as part of a House of Mouse Christmas special. I’ve seen probably dozens of other Christmas Carol adaptations since then, both good (The Muppet Christmas Carol being my absolute favorite) and very, very bad. But this version will always hold a special place in my heart as the very first.

We are introduced to many familiar Disney characters playing the various roles from Dickens’ original story, including Mickey Mouse (Wayne Allwine) as Bob Crachit, Jiminy Cricket (Eddie Carrol) as the Ghost of Christmas Past, Willie the Giant and Pete (both voiced by Will Ryan) as the Ghosts of Christmas Present and Future, Donald and Daisy Duck (Clarence Nash and Patricia Parris) as Fred and Isabelle, Goofy (Hal Smith) as Jacob Marley (try wrapping your head around that one!), and, of course, Scrooge McDuck (Alan Young) as Ebenezer Scrooge (incidentally, Young’s first performance as the character was in an audio only adaptation released a decade before this one).

As a Disney production, it naturally aims for a more family-friendly take on the classic story. For instance, instead of dismissing the charity collectors by cruelly stating that the poor should die and decrease the surplus population, Scrooge instead turns them away using what TVTropes.com calls “insane troll logic” (“If you give money to the poor, they won’t be poor anymore. If they’re not poor anymore, you won’t have to raise money anymore. And if you don’t have to raise money, you’ll be out of a job!”). It also includes a lot more cartoon hijinks than the average Christmas Carol adaptation, especially with the dim-witted Ghost of Christmas Present as he stumbles over London using lampposts as flashlights, and with this adaptation’s version of Marley’s ghost (hey, if you’re gonna have Goofy in this, you have to have him go “YAHHHH-HO-HO-HO-HOOOEEEY!!!!!!” at least once).

The special balances this out, however, by not being afraid to indulge in the darker, more emotional elements of the story where appropriate. The part where Scrooge forecloses on his and Isabelle’s honeymoon cottage for being an hour late on the mortgage (thus sealing the relationship’s fate) is a well-done scene. It is the Christmas Future segment, however, that really stuck in many children’s minds, not only for showing Mickey Mouse crying over Tiny Tim (something that Disney rarely lets happen) and then the Ghost shoving Scrooge into his grave (which turns into a portal to Hell! Jesus…) while cracking cruel jokes at his expense as he begs for his life.

Overall, this is definitely a Christmas Carol adaptation in the vein of the version starring Michael Caine alongside the Muppets: one that smooths out enough rough edges so the whole family can enjoy it while still staying true to the story’s more gothic elements. Like all of Disney’s best creations, it’s a cuddly and heartwarming affair that all ages can enjoy. Sure, Richard Williams’ adaptation still edges it out as the best animated adaptation (fun fact: this version was also nominated for Best Animated Short Film at the 56th Academy Awards but lost to Jimmy Picker’s Sundae in New York), but it’s still essential Christmas viewing nonetheless.

#519: The Nightmare Before Christmas

Animation style: Stop-motion

Release date: October 9, 1993

Distributor: Buena Vista Pictures Distribution

Production companies: Touchstone Pictures, Skellington Pictures

Director: Henry Selick

Writer: Michael McDowell (story); Caroline Thompson (screenplay) (based on characters created by Tim Burton)

Producers: Denise Di Novi, Tim Burton

Music: Danny Elfman

What am I even supposed to say about this movie that hasn’t already been said? It’s possibly second only to Rankin-Bass’ Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer as the most popular piece of stop-motion animation ever made. Indeed, it’s also one of the most popular pieces of media Tim Burton has been associated with (much to the chagrin of Henry Selick, who actually directed the damn thing). But what made The Nightmare Before Christmas such a holiday classic? The story? The characters? The songs? The fact that it fits in so well with both Halloween and Christmas? All of them at once? Well, let’s start with elaborating on the story it tells (for the probably five people in the world who haven’t seen it yet).

In a world where portals exist to the worlds where seven major holidays come from, the residents of Halloween Town have an absolute blast making Halloween happen every year. But trouble arises when the Pumpkin King, Jack Skellington (voiced by Chris Sarandon and sung by Danny Elfman), who feels depressed and stuck in a creative rut, stumbles across Christmas Town and, after spending several sleepless nights trying to understand it, decides that he and the other Halloween ghouls and goblins will take it over this year. Problems quickly arise, as not only is Halloween Town jumping into their yuletide celebration without properly understanding it, but Sally (Cathrine O’Hara), a free-spirited rag doll with a secret crush on Jack, has a psychic vision telling her that his adventure will end in disaster. It doesn’t help that Jack has “Sandy Claws” (Ed Ivory) kidnapped by delinquent trick-or-treaters Lock, Shock, and Barrel (Paul Reubens, O’Hara, and Elfman, respectively), who immediately send him to their master, Oogie Boogie (Ken Page), a sadistic torturer who loves gambling with the lives of his victims, against Jack’s wishes. Can Jack rescue Santa and fix his mistakes before Christmas is ruined for everybody?

One of the things that stunned critics when this film came out was its visual inventiveness. Perhaps the late great Roger Ebert put it best when he said that “there is not a single recognizable landscape in it. Everything looks strange and haunting. Even Santa Claus would be difficult to recognize without his red-and-white uniform.” He goes on to describe the world Burton and Selick crafted as being “as completely new as the worlds we saw for the first time in Metropolis [1927], The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, or Star Wars.” His comparison of this film to Dr. Caligari is entirely appropriate, given Burton’s obvious affinity for German Expressionism. The character designs are just as inventive, from the way the Mayor’s (Glenn Shadix) face switches from a happy one to a sad one depending on his mood swings to the various inventively creepy original creations like the Harlequin Demon’s (Greg Proops) hi-hat-shaped head, the Bat Boy who walks on his spindly wings, and the perpetually melting little man.

Of course, it’s not the visuals alone that make this film so beloved. It’s also one of the most fondly remembered musicals from any Renaissance-era animation. Practically every song has stood the test of time as a bona-fide Halloween/Christmas classic, from the epic opening number “This Is Halloween” (accompanied by an opening sequence so awe-inspiring that it almost makes the rest of the film suck in comparison); to the aching sadness of “Jack’s Lament,” “Sally’s Song,” and “Poor Jack”; to the bright exhuberance of “What’s This?”; and the delighfully macabre “Kidnap the Sandy Claws,” “Making Christmas,” and “Oogie Boogie’s Song.” All of this is held together by Jack’s beautiful singing voice, provided by Danny Elfman.

Indeed, Burton and Elfman admitted to writing the songs first and then building the screenplay around them, as they had no idea how else to approach such an unusual story. Some have argued that the story itself feels half-baked as a result. Oogie Boogie suffers the most from this approach, as he’s not really that essential to the plot except as a place to put Santa while Jack goes off on his merrily morbid adventure.

With a voice cast this good, however, it’s very easy to overlook any deficiencies in the script. Jack and Sally are, to paraphrase Ebert, misfits gifted by fate with quirky personalities that no one else knows what to do with (Burton’s favorite character archetype, as Ebert points out). Jack finds that no one else shares his boredom with the spooks and scares of Halloween, which depresses him, while Sally’s restlessness constantly irritates her overprotective father, Dr. Finklestein (William Hickey), who goes to increasingly desperate lengths to keep her locked up. Indeed, their struggles feel very relatable to people (like myself) who feel trapped in a place they don’t find spiritually fulfilling.

Practically every denizen of Halloween Town is equally vibrant in personality, thanks to their unique designs and skillful voice acting. Oogie Boogie is equal parts hilarious and horrifying thanks to Ken Page’s bombastic performance (“WHAT?!!! YOU TRY AND MAKE A DUPE OUT OF MEEEEE?!!!”). Glenn Shadix gives a perfect performance as the literally two-faced Mayor (I especially love the way Shadix’s voice catches when the Mayor almost falls out of the spotlight booth during the “Town Meeting Song”). Even the minor, unnamed characters get several memorable moments, like one of the witches using her hat as an ear trumpet, the street band being unable to play Christmas carols in a major key, and the zombie clown guy getting swallowed by a python he’s trying to fill as a Christmas stocking during the “Making Christmas” montage.

Even if the story might have needed a little more work, it’s not hard to see why The Nightmare Before Christmas became such a massive cult classic when it’s practically bursting with this much creativity. To quote Ebert one last time, “this is the kind of movie older kids will eat up; it has the kind of offbeat, subversive energy that tells them wonderful things are likely to happen.” It’s the kind of movie that keeps its appeal from October 1st to December 25th and all throughout the rest of the year. I don’t think Burton or Selick could ask for a better legacy than that.

#593: Anastasia

Animation style: Traditional 2D

Release date: November 14, 1997

Distributor: 20th Century Fox

Production companies: Fox Family Films, Fox Animation Studios

Directors/producers: Don Bluth, Gary Goldman

Writers: Eric Tuchman (story); Susan Gauthier, Bruce Graham, Bob Tzudiker, Noni White (screenplay)

Music: David Newman (score); Stephen Flaherty, Lynn Ahrens (songs)

Don Bluth’s take on the longstanding urban legend that the Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna Romanova survived the Russian Revolution, despite the well-publicized murder of the Imperial family on the night of July 16, 1918, has proven somewhat divisive in the years since its release. Fans have hailed it as a return to form for the legendary ex-Disney animator after a long string of critical and financial failures throughout the 90s. Detractors have dismissed it as a blatant attempt to copy the Disney princess formula that makes light of a very real historical tragedy. Regardless, it remains Bluth’s highest-grossing film to date, earning $140 million against a $53 million budget, and has amassed a dedicated cult following.

The film starts with an eight-year-old Anya (voiced by Kirsten Dunst and sung by Lacey Chabert) witnessing the disgraced sorcerer Grigori Rasputin (Christopher Lloyd/Jim Cummings) as he lays a curse on the Romanovs for exiling him. When the Russian Revolution comes, and Bolshevik soldiers bust down the palace gates, Anya and her grandmother, Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna (Angela Lansbury), escape with the help of a young kitchen boy named Dimitri. As they rush to catch a train out of Russia, however, Anya and Maria become separated, with the former suffering a concussion that renders her amnesiac.

Ten years later, a still amnesiac Anya (Meg Ryan/Liz Callaway) is turned out of an orphanage she’s been living in and (inspired by an inscription on a locket Maria gave her) becomes determined to reach Paris and rediscover her past. She receives help from an adult Dimitri (John Cusack/Jonathan Dokuchitz) and his partner, Vladimir Vasilovich (Kelsey Grammer), who seek to find a lookalike for the Grand Duchess so convincing that they can con the Dowager Empress out of her reward money. They will face many obstacles on their journey, including trying to get out of Russia without falling afoul of the Soviet authorities, Maria growing tired of the numerous imposters impersonating her granddaughter and refusing to see any others, and, worst of all, Rasputin, who is stuck in limbo as an undead corpse and determined to put an end to the Romanov line, one way or another.

Obviously, one’s enjoyment of this film will probably depend on how willing you are to tolerate its fast and loose treatment of the historical events that inspired it. While the real Anastasia’s death hadn’t been proven beyond a reasonable doubt when this film came out, DNA analysis of the bodies in 2007 eventually proved that Anastasia was, in fact, killed in 1918 and buried along with the rest of her family. Even before that, though, the film was condemned as in poor taste by several historians, with one even going so far as to compare it to making a film in which “Anne Frank moves to Orlando and opens a crocodile farm with a guy named Mort.” Some of the actual Romanov descendants, including Nicholas II’s grand-niece, Marina Beadleston, felt that the film was “fine so long as somewhere a history book and parents correct it to give how it really happened” and expressed amusement at how overly romanticized the Russian royal family seems to be.

Personally, as a leftist myself (though more anarcho-communist than Marxist-Leninist), I feel more annoyed by the way the Bolsheviks and the Revolution were portrayed. The film seems to imply that the Revolution started because of Rasputin’s curse rather than the harsh political realities of the Czar’s reign (including anti-Jewish pogroms, mismanagement of the Russo-Japanese and First World Wars, and the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1905), thus reducing the Bolsheviks to being pawns of an evil sorcerer. There’s also a rather subtle moment during the “Journey to the Past” sequence, when Anya comes to a fork in the road and is presented with the choice of going left (embracing her life in Soviet Russia) or going right (reclaiming her monarchical heritage). To be fair, this could just be a coincidence, and I don’t know enough about Don Bluth’s politics to dwell on it, so let’s just move on (though if you do want to know more about my personal thoughts on Soviet Russia, I wrote an article on that that you can find here.)

Despite such misgivings, though, I would still readily describe myself as a fan of the film. What can I say? The animation is absolutely gorgeous (it’s a Don Bluth movie. Did you expect anything less?), the music and songs are up there with some of Disney’s best (“Journey to the Past,” “Once Upon a December,” and “In the Dark of the Night” being some of the biggest highlights), and the characters fun and engaging. Anya herself deserves special mention for her snarky dialogue and spunky, determined personality that set her apart from many of the Disney princesses who clearly inspired her. Rasputin is also a great villain, often prone to comical breakdowns whenever his plans go awry, but also still capable of inspiring genuine fear, especially the creepy scene where he uses a dream to try to get Anya to sleepwalk over the side of a ship (though Dimitri snaps her out of it before he pulls it off).

There are some side characters whose treatment by the story feels a bit questionable. For instance, Vlad starts the movie as an unrepentant conman just like Dimitri, yet he receives none of the character development that his younger protege does, which makes his “fun uncle” characterization feel somewhat hollow. Also, Bartok (Hank Azaria), Rasputin’s funny animal bat sidekick, is clearly meant to be viewed as nothing more than quirky comic relief, yet almost gets Anastasia and Maria killed near the beginning while they try to escape down the icy Little Nevka River when he warns Rasputin that they’re getting away (luckily, he falls through the ice and drowns). Granted, he does clearly feel uncomfortable around Rasputin as his master goes further and further off the deep end and entirely abandons him during the climax, but it still may leave a bad taste in one’s mouth that he almost got an innocent child killed and received little to no consequences for it.

Sure, maybe this film is, in Lindsey Ellis’ words, Don Bluth throwing in the towel and saying, “Alright, Disney, you win!” (even Bluth himself admitted that he probably wouldn’t have done a film like this if he hadn’t spent the early 90s in the box-office doldrums). But even if it is a Disney ripoff, it’s a damn good one, and serves as one of the last major hand-drawn animated films ever released in the United States. It is a shame that this film never became the career resurrection that Bluth would have liked (the financial failure of his next movie, Titan A.E., led him to retire from the film industry entirely). Still, it’s good to know that one of America’s greatest animators got to give us one last bona fide classic before the end.

#698: Tokyo Godfathers

Animation style: Traditional 2D

Release date: August 30, 2003

Distributor: Sony Pictures Entertainment Japan

Production company: Madhouse

Director/writer (story): Satoshi Kon

Writers (screenplay): Keiko Nobumoto, Satoshi Kon

Producers: Shinichi Kobayashi, Masao Takiyama, Taro Maki

Music: Keiichi Suzuki, Moonriders

One might be forgiven for thinking that a land as steeped in Buddhism and Shinto animism as Japan wouldn’t have much use for Christmas, but you’d be mistaken. The secular aspects of the holiday are surprisingly popular in the land of the rising sun, and the Japanese have even created their own regional traditions, like a unique recipe for Christmas cake and (of all things) eating KFC chicken. But it’s far from the most wonderful time of the year for the socially outcast and downtrodden, which is what the late great Satoshi Kon sought to emphasize with his entry in the canon of Christmas classics.

We follow three homeless people wandering the streets of Tokyo on Christmas Eve: Gin (Tooru Emori/John Avner), a middle-aged alcoholic who took to the streets to avoid gambling debts; Hana (Yoshiaki Umegaki/Shakina Nayfack), a transgender woman and former lounge singer; and Miyuki (Aya Okamoto/Victoria Grace), a teenager who ran away from home after a violent confrontation with her police officer father (Yusaku Yara/Crispin Freeman). While foraging through a garbage pile, the trio finds an abandoned baby, with Hana (who names the child Kiyoko) making it her personal mission to reunite the child with her parents, despite Gin and Miyuki’s protests that the police are far better equipped to handle such a search. The search brings the trio on a wild adventure packed with several coincidences, Christmas miracles, and experiences that teach the group what family really means.

This film has become notable among Satoshi Kon fans for how it dispenses with the mind-bending psychological horror that characterizes the rest of his work and emphasizes a more wholesome magical realist form of surrealism. It’s less of the David Lynch/Charlie Kaufman style of heightened reality and more like a cross between Love Actually and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia. Indeed, it shares the latter’s fascination with coincidence, which not only seems to confirm the characters’ in-universe suspicions that God has uniquely blessed Kiyoko but also serves as Kon’s way of utilizing the common “Christmas miracle” trope.

The script, co-written by Keiko Nobumoto of Cowboy Bebop and Wolf’s Rain fame, does a great job of emphasizing the plight of Japan’s homeless population while still managing to dig a heartwarming Christmastime adventure out of it. It accomplishes this via black comedy (one particularly subtle and clever one involves a row of lighted windows above Gin during his fight with the teenage deliquents that blink out one by one to represent a video game-style life bar) and making the various contrived coincidences just absurd enough to make you think a supernatural hand might be guiding them, but still just enough within the realm of plausibility to make you not question them too hard.

The characters who bring this screenplay to life are incredibly vibrant and lovable, especially the main trio. Hana deserves special mention for not only being a highly empathetic portrayal of a trans woman (something desperately needed in my home country even today) but also being the most traditionally heroic of the main trio, her kind-hearted and protective nature providing a nice contrast with Gin and Miyuki’s sarcastic cynicism. Don’t get me wrong, though, they prove to be just as good-hearted and protective of Kiyoko when the chips are down.

Tokyo Godfathers may be more grounded and mundane than much of the rest of Satoshi Kon’s work, but it’s just as much of a triumph as Perfect Blue or Paprika. The animation, while less ambitious than the others, is perfect for a film like this. With lovably flawed characters and a story that’s surprisingly sweet despite all the dark subject matter it focuses on, it’s no wonder it’s become a Yuletide cult classic.

#717: The Polar Express

Animation style: Motion-captured CGI

Release date: October 13, 2004

Distributor: Warner Bros. Pictures

Production companies: Castle Rock Entertainment, Shangri-La Entertainment, Playtone, ImageMovers, Golden Mean Productions

Director: Robert Zemeckis

Writers: Robert Zemeckis, William Broyles Jr. (based on the book by Chris Van Allsburg)

Producers: Steve Starkey, Robert Zemeckis, Gary Goeztman, William Teitler

Music: Alan Silvestri

This adaptation of Chris Van Allsburg’s beloved Christmas story is probably best remembered for its innovative animation style, which introduced a new CG approach that used motion capture to achieve a much more realistic look. Unfortunately, that creative decision would also make the film somewhat controversial, as many viewers felt that the result dipped a little too far into the uncanny valley for comfort. I’ve never really felt that way myself…though maybe that’s just the nostalgia talking.

The story begins in Grand Rapids, Michigan, sometime in the 1950s or 60s, where our young, unnamed main character (Daryl Sabara) has started to doubt Santa Claus’s existence. One can imagine his shock when the eponymous steam engine shows up in front of his house, with its Conductor (Tom Hanks) offering to take him and several other children to the North Pole, where Santa (also Hanks) will choose one of them to receive the first gift of Christmas. What follows is a whimsically surreal adventure through the snowy, frozen north, where our doubting Thomas goes on a journey of self-discovery and learns valuable truths about friendship, bravery, and Christmas spirit.

Okay, so I know I said that this film doesn’t give me the uncanny valley heebee jeebees, but I may have been lying to myself a bit. There are a few spots where the creepiness gets to me (the scene where Know-It-All Kid (Eddie Deezen) is introduced being the worst example (ewww, stop looking directly into the camera like that!). Also, the Steven Tyler elf jump scare.). Even beyond the unintentional creepiness, it was clear to me during my most recent rewatch that the animation is really starting to show its age (it’s been over twenty years. What did you expect?).

There are other elements of the film that used to be non-issues but have started to bother me more and more as I’ve grown older. For example, the fact that none of the children get any characterization probably worked better for me when I was their age, in a sort of audience-surrogate self-insert kind of way. Nowadays, though, I find myself wanting to know why Christmas never works out for Billy (Jimmy Bennett) or wanting to know…hell, anything about the Hero Girl (Nona Gaye). That’s not even getting into how inconsistent the ghostly Hobo (also also Hanks) is. One minute, he’s seemingly agreeing with Hero Boy’s skepticism of Santa Claus and saving him from certain destruction on a regular basis; the next, he’s using a Scrooge marionette to scold him for doubting St. Nick’s existence (seriously, I cannot for the life of me figure out what the point of that scene was).

I get it. The film is less focused on the characters and more focused on letting the cool magic train do cool magic stuff. The thing is, while the stuff the Polar Express accomplishes is entertaining to watch in the moment (the scene where the train Tokyo-drifts across the ice lake will probably never stop being awesome), there’s also a voice at the back of my head asking, “Did we really need to see the train tracks turn into a rollercoaster? Did we need to have that scene where the Hobo skis down the car roofs? Did we need to have Santa’s sack be so big that it needed an airship to lift it?” Indeed, all this focus on action and spectacle feels especially out of place when one remembers how calm and relaxing the original book’s story was.

While a lot of this might be a dealbreaker for several viewers, I find that the film has enough redeeming qualities to help me (somewhat) forgive these faults. Alan Silverstri’s score is expertly crafted (even if some themes are a little overused). The songs are a bit hit and miss; “When Christmas Comes to Town” has kind of lost its luster, but “Hot Chocolate” is still fun, and Josh Groban’s “Believe” is still one of the most beautiful modern Christmas songs. And the story, for all its attempts to jam over-the-top action setpieces into a story that doesn’t really need them, still preserves enough of the dream logic present in the book to save it from being an in-name-only adaptation. Best of all, of course, is Hanks’ lively and boisterous performance as the Conductor.

Indeed, the whole reason the movie was made in the first place was that Tom Hanks read the book to his kids one day and decided he really wanted to play the Conductor. Still, when Hanks was starting his quest to get The Polar Express adapted as a film, his first choice to direct was Rob Reiner (rest in peace, king). I would have loved to see what he would have done with it.

In summation, while the film adaptation of The Polar Express might have lost some of its magic as I’ve grown older, there’s still enough charm for me to argue that it still deserves its place as a Christmas classic. Still, if I had to choose any animated film involving a supernatural train, I’d probably select Night on the Galactic Railroad over this.

#877: Frozen

Animation style: 3D CG

Release date: November 19, 2013

Distributor: Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures

Production company: Walt Disney Animation Studios

Directors: Chris Buck, Jennifer Lee

Writers: Chris Buck, Jennifer Lee, Shane Morris (story); Jennifer Lee (screenplay) (inspired by “The Snow Queen” by Hans Christian Andersen)

Producer: Peter del Vecho

Music: Christophe Beck

Our second interpretation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” is undoubtedly the most popular film Disney has released this century so far. But does it live up to the hype, or has time revealed it to be less good than we thought? My TL;DR is that it’s not a bad movie by any means, but it still has significant flaws that hold it back.

Our Snow Queen in this version is not the imposing godlike femme fatale from the 1957 Soviet film, but rather Elsa (Idina Menzel), the eldest daughter of the king and queen of the fictional Scandinavian kingdom of Arendelle, who possesses magical ice powers that she struggles to control. To add to her struggles, she’s been forced to keep her powers a secret after almost accidentally killing her younger sister Anna (Kristen Bell), leading the king and queen to isolate her from Anna and the rest of the kingdom. Their dying in a shipwreck doesn’t help matters. During Elsa’s coronation ceremony, a fight between the sisters, caused by years of being isolated from each other and Elsa refusing to bless an engagement between Anna and Prince Hans of the Southern Isles (Santino Fontana) (whom she literally meant just that evening), causes Elsa to accidentally reveal her ice powers to the kingdom. Elsa runs away to the mountains to start a new life on her own, but her power incontinence causes a snowstorm that threatens to bury Arendelle. Thus, Anna sets out on a quest, assisted by ice harvester Kristoff (Jonathan Groff), his doglike reindeer Sven, and a sentient comic-relief snowman named Olaf (Josh Gad), to bring her sister back and bring summer back to Arendelle.

In the decade-plus since its release, now that the hype has died down, some have derided this film as an overrated mess and one of the worst films Disney has ever put out. I don’t agree with those critics, but I also don’t agree with those who think this is Disney’s best film since The Lion King. I think Frozen is both overrated and overhated at the same time.

There is plenty to like about this film. The animation does a fantastic job of bringing both the snowy Scandinavian landscapes and Elsa’s beautifully rendered ice powers to life. The characters are fun and likable, especially Anna and Olaf. I know a lot of viewers find Josh Gad's snowman annoying, but I think he works well as comic relief, especially during his morbidly naive number “In Summer.” Speaking of which, I also really love (most of) the songs and music. “Let It Go” may be somewhat overplayed, but it became a classic for a reason. The film has many other great tracks if you’re sick of that one, from “Frozen Heart” and “Love Is an Open Door” to “For the First Time in Forever” and “Do You Want to Build a Snowman?”

Probably the only song I actively dislike is “Fixer-Upper,” primarily because of how pushy and annoying the trolls are during the song. Their leader, Pabbie (Ciaran Hinds), is annoying for entirely different reasons, as his solution to saving Anna from the magical accident at the beginning (literally erasing Anna’s memories and telling the king and queen to isolate Elsa until she learns to control her powers) directly leads to most of the problems Anna and Elsa face throughout the plot, including Elsa’s emotional repression and isolation and Anna’s naivete, which Prince Hans is easily able to exploit.

Speaking of which, though, Hans is easily the worst part of this film. The twist that the Prince is evil all along is meant to be a clever subversion of the “Prince Charming” archetype familiar in many Disney movies, which would be totally fine if not for the fact that it is not well foreshadowed at all. Hans’ behavior before the reveal doesn’t read like a manipulative schemer, but after, he completely 180’s into a mustache-twirling villain who gloats to Anna about how he’s going to leave her to freeze to death and then kill Elsa to secure his spot on Arendelle’s throne. Except, if that was his plan all along, then why did he not just let the Duke of Weselton’s (Alan Tudyk) guards kill her outright when they stormed her ice palace instead of trying to reason with her? I understand that the writers were trying to make a point that an act of familial love is just as valid as a “true love’s kiss,” but surely there was a better way to go about it than this?

Indeed, this might be a big reason why so many have turned against this film over the years: it included several tropes that Disney used so much in subsequent films that they quickly beat them into the ground (poorly handled twist villains, a focus on generational trauma as the central conflict, queer reperesentation being glorified cameos that can easily be cut for the Chinese market, etc.).

For better or worse, though, Frozen has earned its place in animation history for its overwhelming popularity, enough to make it the highest-grossing animated film of all time when it was first released, although it has since slipped to seventh place, with even its own sequel outgrossing it. Sure, I’d probably pick Tangled or Encanto over it, as those films have much more cohesive stories. Still, a 6/10 Disney film is better than Wish any day of the week.

#994: The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse

Animation style: Traditional 2D

Release date: December 24, 2022

Distributors: Apple TV+, BBC One, BBC iPlayer

Production companies: Apple Studios, Bad Robot Productions, NoneMore Productions

Directors: Peter Baynton, Charles Mackesy

Writers: Jon Croker, Charles Mackesy (based on Mackesy’s children’s book)

Producers: Cara Speller, Matthew Freud, Hannah Minghella, J. J. Abrams

Music: Isobel Waller-Bridge

Figuring out how to describe this short is rather difficult, given the rather ambitious range of philosophical subject matter it seeks to tackle. Perhaps IMDb reviewer A_Different_Drummer put it best: “It is an adventure, it is a drama, it is a fable, it is animation for kids, it is animation for adults, and it is also a morality tale.” It might also rank alongside Tokyo Godfathers as one of the greatest found-family narratives in all of animation.

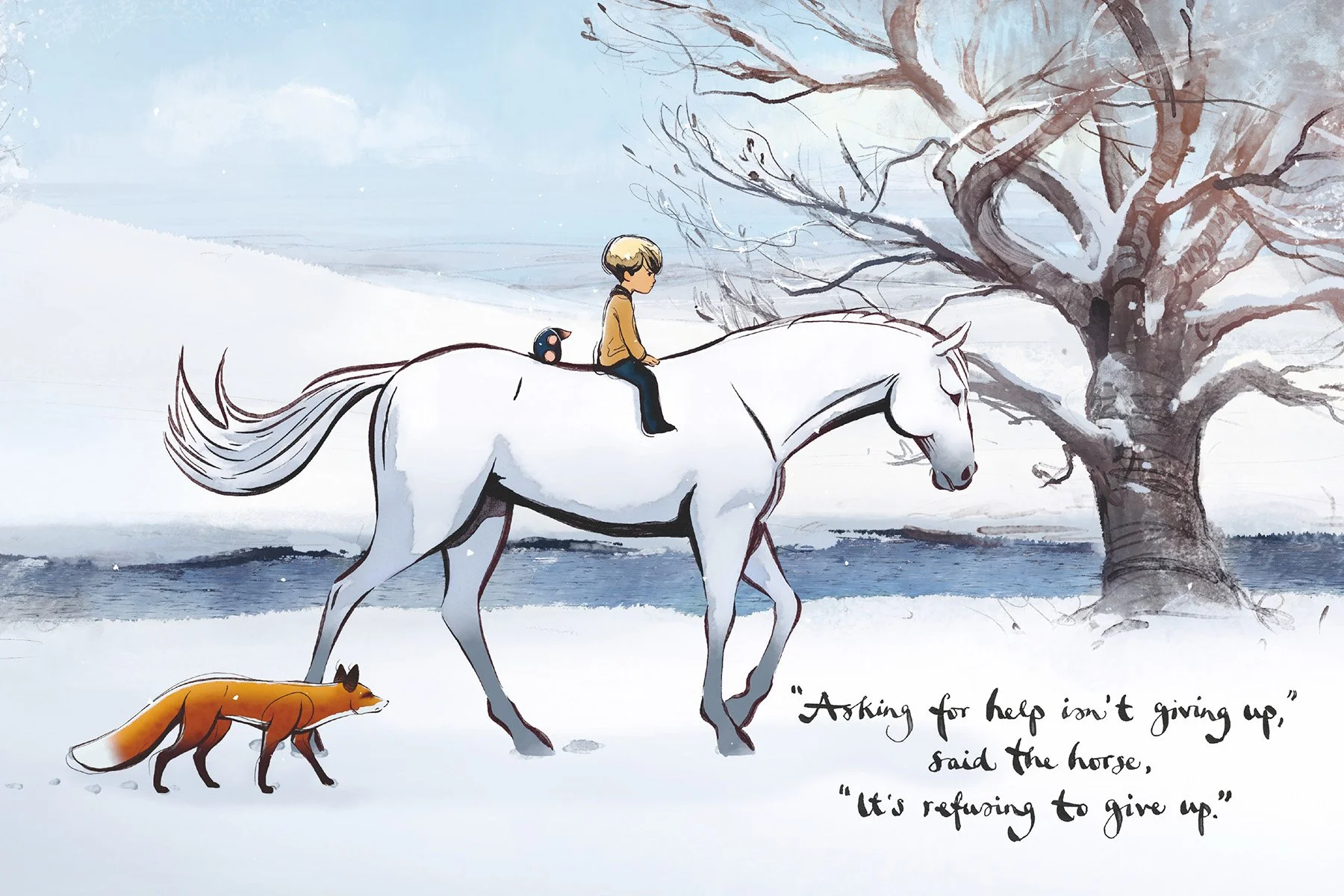

Based on the best-selling 2019 picture book, it follows a boy (Jude Coward Nicoll) who is wandering a snowy landscape with no memory of who he is or where he came from. As he journeys to find a place he can call home, he befriends three talking animals: a mole (Tom Hollander) whose obsession with cakes becomes a running gag, a fox (Idris Elba) who starts as an enemy but befriends the duo after they rescue him from a snare, and a soft-spoken white horse (Gabriel Byrne) who quickly becomes a father figure to the lost boy. As they try to reach the lights of a distant village, they ponder big, existential questions about hope, friendship, love, kindness, and what it really means to be “home.”

This film could be said to occupy a similar whimsically surreal space as The Polar Express, introducing several fantastical elements that are mostly unexplained while telling a calm, relaxing story. What sets it apart, however, is its strong focus on philosophy, almost enough to make it a spiritual successor to The Little Prince. The dialogue is peppered with sagely aphorisms, which could easily have come off as preachy, but are delivered here with a poigniant tenderness and sincerity, especially when Gabriel Byrne’s horse delivers them. For example, when the boy falls off the horse’s back into a creek and starts crying, he assures the boy that “Tears fall for a reason, and they’re your strength, not weakness.” Later, when the boy asks the horse what the bravest thing he ever said was, the horse responds, “Help. Asking for help isn’t giving up. It’s refusing to give up.” That’s a lesson I’ve had to take to heart recently as my mental health struggles have started to catch up with me (Incidentally, I’ve managed to connect with an online therapist recently, and I’m really liking her so far!).

If there is one very mild criticism I could make about the short, it’s the way the problem of reaching the village is solved. I don’t want to spoil too much, but the gist is that the horse reveals a secret that he’s reluctant to disclose because of how jealous the other horses became over it. Cynics could dismiss this as a deus ex machina. However, given how much the secret ties into the story’s themes of friendship and acceptance, and how it helps strengthen the bond between our plucky group of misfits, I think it’s appropriate to let it slide.

Besides, the other elements of this special are so good that it definitely makes up for it. It has a unique 2D art style that perfectly mimics the book’s sketchy illustrations. It offers wonderful life lessons that both children and adults can find meaningful. Best of all, it provides a perfectly uncomplicated story in which to deliver these lessons, capped off by an unexpected conclusion that might just have you crying tears of joy.

It might not have several of the aesthetic elements of a Christmas special, but it’s still likely to become a holiday classic all the same. Indeed, I think this quote from the mole is a good candidate for the true meaning of Christmas: “Nothing beats kindness. It sits quietly beyond all things.”

Well, I didn’t achieve my goal of getting this out before Christmas. Obviously, things got hectic for me during the big week. I didn’t complete my Christmas shopping until that Monday, and I was often occupied in the days that followed, helping my parents get ready for the big family get-together on Christmas morning. Still, better late than never, right?

I don’t have much left to say about the list. I hope it’s given you some new winter-themed classics to enjoy during the holiday season. Indeed, I hadn’t seen The Snow Queen or Tokyo Godfathers before I made this list. I’ll have plenty more animation-themed commentary to give as 2025 fades into 2026, but I’d rather save the details for my New Year update post, which will be coming out later this week.

Until then, stay safe, have a happy holiday season, and remember: don’t piss off the Snow Queen!